Counting combinations

I was reading Bishop’s book Deep learning, and was once again reminded of the equation for calculating the number of k-combinations, equivalent to the binomial coefficient

\[\frac{n \cdot (n-1) ... \cdot (n-k+1)}{k!} \quad (1)\\ = \frac{\color{blue}{\frac{(n-k)!}{(n-k)!}} \cdot n \cdot (n-1) ... \cdot (n-k+1)}{k!} \\ = \frac{\color{blue}{(n-k)!} \cdot n \cdot (n-1) ... \cdot (n-k+1)}{k!\color{blue}{(n-k)!}} \\ = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!} \quad (2)\]Above is the formula both in its more gauche form (Eq. 1) and its more commonly used form (Eq. 2). Looking at it got me thinking that it’s sort of a funny looking equation to always produce a whole number. Right? If, for some combination of n and k, the numerator was not divisible by the denominator, we would have a fraction. Obviously, this wouldn’t be right.

Just for a moment forget everything you know about what Eq. 2 is doing. Naively looking at the formula this way, there is no immediately obvious reason as to why three factorials in this arrangement would always produce a whole number, at least to me.

It’s important to note that the formula is only valid for $n \in \mathbb{N}_0$ and $0 <= k <= n$, where $k \in \mathbb{N}_0$ is also a whole number. In case $k > n$, the second factorial in the denominator is taken of a negative number. In case $n < 0$, the one in the numerator arrives at a similar situation. Of course, the factorials can’t be chosen arbitrarily either:

\[\frac{7!}{5!4!} = 1.75\]Laying the groundwork

I’ve always found the Eq. 1 to have the superior optics despite its lack of notational tidiness. It can be thought of like this:

\[\frac{\text{In how many ways can we choose k items from a set of n items without replacement?}}{\text{How many ways are there to order a set of k items?}}\]So when sorting a set of $k$ items, we choose the first item in our ordering from $k$ options, then the second item from $k-1$ options, and so on. Just like when we choose the items themselves from $n$ options in the numerator. Another way to look at it is this:

\[\frac{\text{In how many ways can we choose k items from a set of n items without replacement?}}{\text{What is the size of subsets of duplicates in the above mentioned set?}}\]Here, a subset of duplicates stands for a subset of items that contains the same elements, albeit in a different order. For example, $\binom 5 3$ is equal to \(\frac{5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3}{3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1} = \frac{60}{6}\). This means that there are a total of 60 ways to form a subset of 3 items from a set of 5 items. For each such subset, there are 5 others which have the same items but in a different order. The sizes of these subsets of duplicates of course remain the same for each unique set of items. Concretely, if we have the set of integers $[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]$, for each subset like $[1, 2, 3]$ there are 5 others which only differ in ordering:

\[[1, 3, 2] \\ [2, 1, 3] \\ [2, 3, 1] \\ [3, 1, 2] \\ [3, 2, 1] \\\]So therefore we divide by 6, as the unique subsets are one sixth of the total. Similarly, there are six ways to order any list consisting of 3 items, so we divide by that. Obvious enough, but we’re trying to make sense of the equation, not the fact that counting subsets produces a whole number.

Baby steps

My first idea in proving this to myself leaned heavily on the number of ways to choose $k$ ordered subsets, ie. the total number of subsets of $k$ items (k-permutations), as opposed to the number of unordered subsets (k-combinations). The binomial coefficient has this equality: $\binom n k = P(n, k) \cdot \frac 1 {k!}$, where $P(*, *)$ stands for the number of ordered subsets. Reasonably then, the total number of $k$-sized subsets is always divisible by the number of ways to order $k$ items, because every unique subset is “overcounted” by a factor of $k!$ in the ordered count. Dividing by $k!$ only cancels this “overcount”, ensuring the binomial coefficient is a whole number.

In other words, we can break down the ordered subsets into equivalence classes, where two subsets are considered equivalent if they consist of the same items. This is the definition of the previously mentioned subsets of duplicates. Each of these equivalence classes contain $k!$ items. Now, there is a perfect partition from subsets of $k$ items into these sets of $k!$ elements representing the unordered subsets. By dividing the number of items contained in all equivalence classes by the size of the (identically sized) equivalence classes, we arrive at the number of equivalence classes, or nodes on the other side of this bijective relationship from unordered subsets to equivalence classes. This must be a whole number.

Expressed most simply, each unordered subset adds $k!$ ordered subsets, so dividing the number of ordered subsets by $k!$ cannot result in a fraction. This is a sort of a double counting-esque way to arrive at the fact that the number of combinations must be a whole number.

But this answer, while being a totally reasonable example of an answer to a course assignment, does not actually provide a meaningful answer. First of all, we’ve just shifted the burden of whole number-ness to the total number of subsets, with the awfully similar looking equation of $\frac {n!} {(n - k)!}$. Secondly and more importantly, we’re not even looking at the equation anymore. All we’re doing is adding more context to an answer that already made sense when observed in context.

For such an obvious sounding question it was quite annoying that the first answer I reached for was as clear as mud. If you really want to run with this approach until the wheels come off, I suspect the proof could also be expressed with the orbit-stabilizer theorem familiar from group theory. However, in terms of tangible intuition this would be the equivalent of attempting to clear up our little mud puddle by dumping a truckload of sand in it. Consequently, I started thinking of all the ways to prove to myself that the formula never produces a fraction. This was hoping that one of them would hit the nail on the head and this property would become obvious. Let’s have a look.

“It’s counting things”

The equation counts things. All formulas that count things output whole numbers. In terms of proofs, this should be enough for even the pettiest level of academic nitpicking. Extra points for saying that it counts subsets or something along these lines. Even if you’re not going to be all that formal about things, you might as well still pretend like you are.

However, as mentioned before, this statement does nothing for building intuition for the equation, and that’s what were aiming for.

Pascal’s triangle

What if we show that the formula generates Pascal’s triangle and each of its outputs can be found in said triangle? As the values in the Pascal’s triangle are always sums of whole numbers, the outputs of the formula must therefore be too.

In Pascal’s triangle, the $n$th row’s $k$th value is equal to $n \choose k$. Obviously, this already proves what we are trying to say, as the Pascal’s triangle quite literally is “a triangular array of the binomial coefficients”. But again, just saying such things has nothing to do with the equation, which is all we’re interested in.

In a visual sense, the topmost value of the triangle is defined as being 1. All consecutive numbers can be thought of as having been generated by summing the two values directly above it, or just the one that is available if we are at the edge. What you get is this [1]:

More formally, the boundary cases are \(\binom n 0 = \binom n n = 1, \forall n \in \mathbb{N}_0\). Then, the $n$th row’s $k$th value such that $n \in \mathbb{N}_+$ and $0 < k < n$ are calculated as follows:

\[\binom {n - 1} {k - 1} + \binom {n - 1} k\]This is known as the Pascal’s identity, Pascal’s rule or Pascal’s formula, depending on who you ask. Either way, now we have a target. Quickly making sure that this is equal to our equation:

\[\binom {n - 1} {k - 1} + \binom {n - 1} k \\ = \frac{(n-1)!}{(k-1)!(n-\bcancel{1}-k+\bcancel{1})!} + \frac{(n-1)!}{k!(n-1-k)!} \\ = \frac{(n-1)!}{(k-1)!(n-k)!} + \frac{(n-1)!}{k!(n-1-k)!} \\ = \frac{(n-1)!\color{blue}{\cdot k}}{(k-1)!(n-k)!\color{blue}{\cdot k}} + \frac{(n-1)!\color{blue}{\cdot (n-k)}}{k!(n-1-k)!\color{blue}{\cdot (n-k)}} \\ = \frac{(n-1)!\color{blue}{\cdot k}}{k!(n-k)!} + \frac{(n-1)!\color{blue}{\cdot (n-k)}}{k!(n-k)!} \\ = \frac{(n-1)! (\bcancel{k} + n - \bcancel{k})}{k!(n-k)!} \\ = \frac{(n-1)! \cdot n}{k!(n-k)!} \\ = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!} \\\]Seems about right. Therefore, we can break down each binomial coefficient with the above equality until it consists of simple sums between the boundary cases, ie. becomes a sum of ones. So for instance, $\binom 5 3$ can then be broken down as follows:

\[\binom 5 3 \\ = \binom 4 2 + \binom 4 3 \\ = \binom 3 1 + \binom 3 2 + \binom 3 2 + \bcancel {\binom 3 3} \\ = \bcancel {\binom 2 0} + \binom 2 1 + \binom 2 1 + \bcancel {\binom 2 2} + \binom 2 1 + \bcancel {\binom 2 2} + 1 \\ = 1 + \bcancel {\binom 1 0} + \bcancel {\binom 1 1} + \bcancel {\binom 1 0} + \bcancel {\binom 1 1} + 1 + \bcancel {\binom 1 0} + \bcancel {\binom 1 1} + 1 + 1 \\ = 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1+ 1 + 1 + 1 \\ = 10\]This is sort of nice. But for me, this didn’t evoke that moment of enlightenment I was looking for. Linking that original form of $\frac{5!}{3!2!}$ or $\frac{5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3}{3!}$ to this sum of ones does not click. If it does for you, that’s great. For me, it’s a swing and a miss.

Good ol’ induction

Some years ago I came across a quote that went along the lines of: Even when we have no idea why a statement is true, we can still prove it by induction. People seem to attribute it to a mathematician named Gian-Carlo Rota, but there’s at least a handful of variants. The idea being that even if we don’t fully (or in the slightest) grasp the underlying intuition or “why” a statement is true, we can still establish its validity by induction. I guess doing this wouldn’t hurt. Who knows, maybe it even helps.

The base case is covered by the previously mentioned realization that $\binom n 0 = \binom n n = 1, \forall n \in \mathbb{N}_0$, and more specifically by the fact that $\binom 0 k$ equals 1 for all possible $k$ (ie. $k=0$).

Now we just need to show that $\binom {n+1} k$ is a whole number as long as $\binom n k$ is one. This is performed by the induction step, where we now assume (assisted by our base case) that $\binom n k$ is a whole number for each k. Back to shuffling Pascal’s identity around, we have

\[\binom n k = \binom {n -1} {k - 1} + \binom {n - 1} { k } \leftrightarrow \binom {n + 1} {k} = \binom {n} {k - 1} + \binom {n} { k }\]Because we know from the induction assumption that $\binom n k$ is a whole number for each k, the right side must be a sum of whole number and therefore $\binom {n + 1} k$ is also a whole number.

Although this provides some more mathematical rigor to our question (which required none of it to begin with), it doesn’t really do much in terms of answering our question. Our base case could also be seen as incomplete, as it covers the only scenario where $k$ has only one valid value.

What are we actually doing here?

This isn’t really going anywhere. It feels like we’re proving things for the sake of proving things and not gaining any meaningful ideas about the equation itself in isolation, as was our goal. Let’s start over and think about this from the top.

Circling back, let’s think of Eq. 1 in the following way:

\[\frac{\text{product of a chain of k consecutive natural numbers}}{k!}\]The denominator is the product of consecutive natural numbers from 1 to k. When thinking of any natural number $n$ and the number line, we first have $n$, then after $n-1$ numbers we have $2 \cdot n$, next is $3 \cdot n$ and so on:

So the number’s multiples appear with a period of $n$. The cyclical nature of this can also be emphasized as a circular Turing machine of sorts:

This has the following consequence:

Lemma 1: Any set of consecutive natural numbers $A \in \mathbb{Z}$ with length $n$, must contain exactly one occurrence of a value divisible by $n$.

This should make intuitive sense. Multiples of $n$ appear every $n$ consecutive numbers, and $n$ consecutive numbers contains, well, $n$ consecutive numbers. The set would have to contain $n+1$ numbers to hold more than one multiple of $n$, and $n-1$ numbers to hold none in some cases.

Is this starting to come together? Here’s a formal-ish way to prove that the formula can only ever produce whole numbers.

Proof: As per Lemma 1, the $k$ consecutive natural numbers in the numerator must include at least one multiple of all values in the set $[1, 2, …, k]$. Therefore, for each value $q \in [1, 2, …, k]$ in the denominator’s product, there always exists a value $v$ in the numerator with factorization $q \cdot x_v$, where $x_v \in \mathbb{Z}$ is some multiplier. Canceling out all such values $q$ from the numerator and denominator leaves a product of whole numbers, which must always produce a whole number.

Let’s work through an example:

\[\binom 5 3 \\ = \frac{5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3}{\bcancel{1} \cdot 2 \cdot 3} \\ = \frac{5 \cdot \bcancel{2} \cdot 2 \cdot \bcancel 3}{\bcancel 2 \cdot \bcancel 3} \\ = 5 \cdot 2 = 10\]One more for good measure:

\[\binom {17} 5 \\ = \frac{17 \cdot 16 \cdot 15 \cdot 14 \cdot 13}{\bcancel{1} \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \cdot 5} \\ = \frac{17 \cdot (4 \cdot \bcancel 4) \cdot (\bcancel 3 \cdot \bcancel 5) \cdot (\bcancel 2 \cdot 7) \cdot 13}{\bcancel 2 \cdot \bcancel 3 \cdot \bcancel 4 \cdot \bcancel 5} \\ = 17 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 7 \cdot 13 = 6188 \\\]This is exactly the neat and intuitive interpretation I was looking for. By the periodicity of natural numbers, the denominator must always cancel out.

For extra flair, remember that the fundamental theorem of arithmetic states that every positive integer greater than one is the product of some prime numbers. This product is unique, barring the ordering of said prime numbers. Just like any natural number $n$ has its multiples appear every $n$ consecutive numbers, so does its prime factorization $p_1^{m_1} p_2^{m_2} (…)$. Therefore, you could also do the same with prime factorizations:

\[\binom {17} 5 \\ = \frac{17 \cdot 16 \cdot 15 \cdot 14 \cdot 13}{\bcancel{1} \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 4 \cdot 5} \\ = \frac{17 \cdot (4 \cdot \bcancel{2^2}) \cdot (\bcancel 3 \cdot \bcancel 5) \cdot (\bcancel{2} \cdot 7) \cdot 13}{\bcancel 2 \cdot \bcancel 3 \cdot \bcancel {2^2} \cdot \bcancel 5} \\ = 17 \cdot 4 \cdot 7 \cdot 13 = 6188 \\\]If you were to use this approach, you might be able to write a proof using Legendre’s formula. This could progress along the lines of “The power of prime $p$ in the prime factorization of the denominator cannot be larger than its counterpart in the prime factorization in the numerator $\forall p \leq n$”, and so on. However, this would be past the point for my purposes and not any more convincing.

Sources

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pascal%27s_triangle#/media/File:PascalTriangleAnimated2.gif

Appendix

As I was finishing the induction proof, I got distracted by another simple question that popped into my mind. This detour was the reason for landing on the eventual explanation for the original question, but it was also unrelated to such an extent that I won’t add it to the main text. Here was the question:

Can the sum of two primes also be prime?

This is a nice question to check how much you remember from number theory. I recommend you think about it for just a moment. Having not worked much with primes for some years now, my immediate thought was “primes are always odd and two odd values sum to an even number, which is then not prime”. This thought of course crashed and burned half a second later at the very first acid test: 2 and 3 immediately sum to 5. The number 2 being prime is an exception to that otherwise valid supposition.

This embarrassing slip had the (fortunately valid) result that for all the primes that are the sum of two primes, one of the two primes summed must be 2. Therefore, the simplest way to know if a prime is the sum of two primes is to check if the number two units below it is prime. These two questions are in fact equivalent.

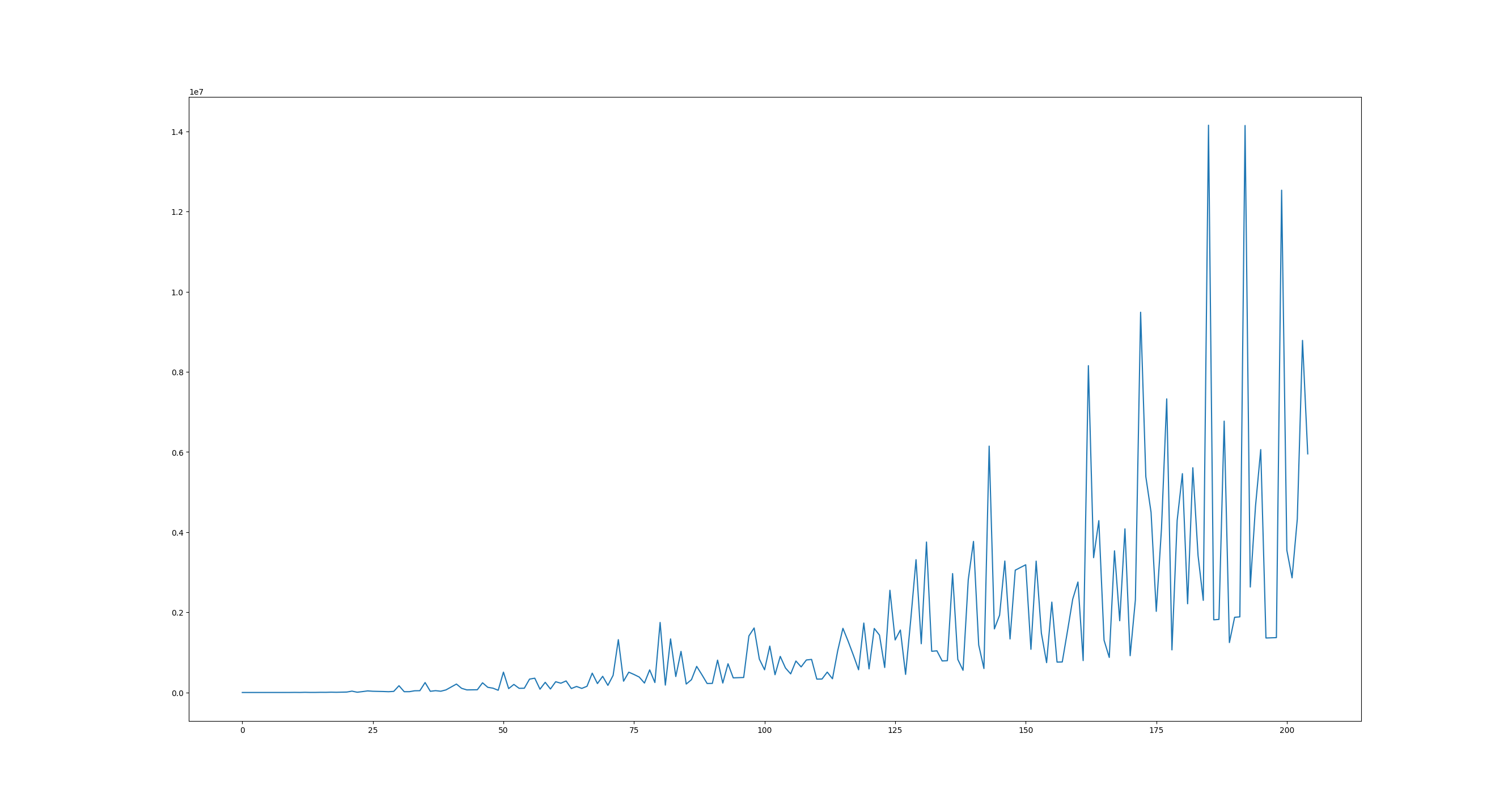

So how frequent are these “primes that are the sums of two other primes”? Let’s do a quick sanity test. Here are the primes below 1000 that are the sum of two primes:

\[3 + 2 = 5 \\ 5 + 2 = 7 \\ 11 + 2 = 13 \\ 17 + 2 = 19 \\ 29 + 2 = 31 \\ 41 + 2 = 43 \\ 59 + 2 = 61 \\ 71 + 2 = 73 \\ 101 + 2 = 103 \\ 107 + 2 = 109 \\ 137 + 2 = 139 \\ 149 + 2 = 151 \\ 179 + 2 = 181 \\ 191 + 2 = 193 \\ 197 + 2 = 199 \\ 227 + 2 = 229 \\ 239 + 2 = 241 \\ 269 + 2 = 271 \\ 281 + 2 = 283 \\ 311 + 2 = 313 \\ 347 + 2 = 349 \\ 419 + 2 = 421 \\ 431 + 2 = 433 \\ 461 + 2 = 463 \\ 521 + 2 = 523 \\ 569 + 2 = 571 \\ 599 + 2 = 601 \\ 617 + 2 = 619 \\ 641 + 2 = 643 \\ 659 + 2 = 661 \\ 809 + 2 = 811 \\ 821 + 2 = 823 \\ 827 + 2 = 829 \\ 857 + 2 = 859 \\ 881 + 2 = 883 \\\]Quite a few, and all follow our realization that the number 2 must be one of the summed primes. Trying to grasp at any periodicity, let’s look at their distances. In the below plot, the values on the x-axis stand for the indices in the list of primes that are the sums of two primes. So if the $m$th prime is the $n$th prime to be the sum of two primes, then it is at the $n$th value on the x-axis. The y-axis stands for how many total primes occurred between this and the previous such prime, ie. the total number of primes between the $n$th and $(n-1)$th prime that are the sum of two primes. We count up to 10000, resulting in 1229 primes and 205 primes that are the sum of two other primes. Fingers crossed for a smooth exponential curve.

The distances explode right out of the gate in very erratic fashion. Conjectures about prime numbers never fail in their ability to elude simple answers.

The mathematically savvy may notice something amusing here. This naive question is a backwards way to arrive at something much more profound, namely the twin prime conjecture. Primes two units apart are called twin primes, and studies into them have yielded at least a couple of Field’s medals for their authors. The twin prime conjecture states that there must be an infinite number of twin primes. This statement remains unproven, although it is stongly postulated. Answering my question of “How frequent are primes that are the sum of two primes” would amount to solving the twin prime conjecture. Whoops.

This thought on primes led to the Sieve of Eratosthenes popping into my mind. One of the most famous ancient methods for forming primes, this algorithm starts by writing out all numbers from 2 onwards.

Then, we mark 2 as prime and mark each multiple of 2 as composite. This is to say, we mark 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and so on as composite. After all, these are multiples of the number 2 and therefore cannot be prime.

Now, we find the smallest number that has not been marked as composite, and mark it as prime. In this case, it will be 3. We repeat the process for 3, marking 6, 9, 12, 15 and so on as composite.

And then 5…

This could then be repeated until we reach the number whose primeness we are trying to evaluate. Relying solely on the periodic nature inherent in the multiplicity of natural numbers, you can theoretically infer if any given number is prime or not.

This idea of the Sieve of Eratosthenes is what got me thinking about the periodicity of the numbers in the binomial coefficient’s denominator. This idea then led to noticing how they cancel out. Truly one of the rare instances where having the attention span of a nematode turns out to be beneficial.