Fortran out here impressing

There’s this visualization of programming language performance benchmarks that I’ve been seeing more recently. Usually it’s posted on some social media platform along with a caption

that either touts the fastest language or vilifies slowest one. Here’s an example of a linkedin post [3] where the visualization is supposedly comparing how

fast different languages are at calculating the Levenshtein distance. Otherwise known as the edit distance, this can be used as a measure of how similar two strings are and is

not trivial to calculate. Let’s see what they have to say:

I can’t get enough of this quote from the post: “Fortran out here impressing”. In these visualizations, the fastest languages are on the top and the slowest on the bottom. In case the bouncing circles aren’t enough of an indicator, there’s also some numbers in

milliseconds on the left. All very scientific. And on the surface, sure, Fortran “do be out here impressing”. After all, it’s the fastest language in the visualization. This is until you

realize that their Fortran implementation was actually truncating the strings to 100 characters, making the problem drastically less difficult and the results completely different. This bug was copied and pasted into many such visualizations because no one’s actually read the code.

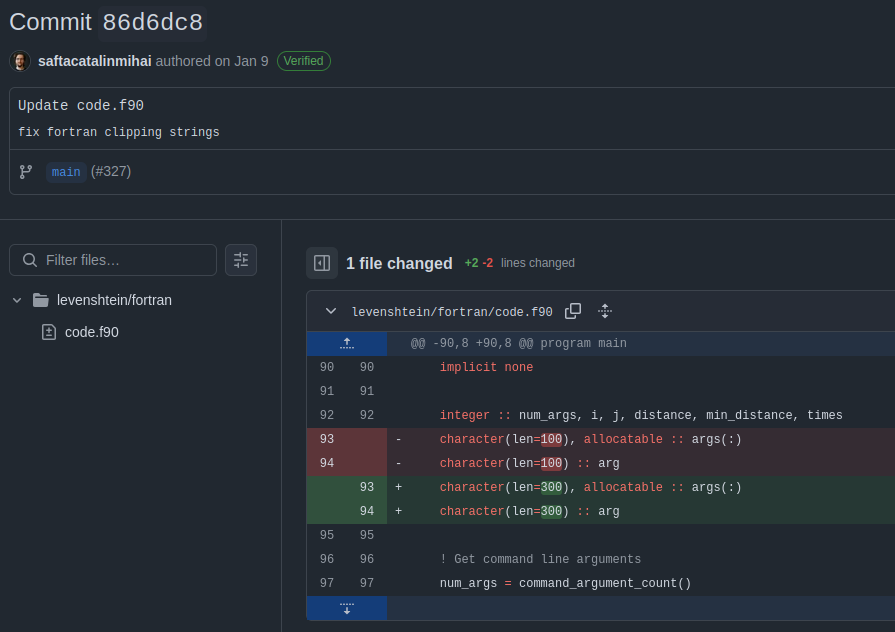

But don’t worry, it was fixed in another repository (not the one from the above video) in a silent 1 file commit with the gracious message of Update code.f90:

The only thing that remains is all the discussion about how Fortran is out here impressing. I’m not sure this is what Winston Churchill meant when he announced that “A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on.”

I find this entire thing baffling. I came across this again because I was having a discussion about computational efficiency with someone and asked if they’d come across the Levenshtein distance visualization mess from the first video. They hadn’t, so I looked it up, and lo and behold there’s more. A lot more. For some reason these visualization are a popular thing to make, debate and share around. Let’s see what else is in store.

After fixing the string truncation problem you get another result where Fortran is slower, as you’d expect. Right now after all these fixes and clarifications, one website [1] centered around showing these things has arrived at a visualization where C++ is almost 20% slower than C and Fortran is still on top.

Why? Who knows. What does this have to do with anything that you’d actually run in production? Ah, but this is the “legacy run” version where start times are included. What does this mean, how much does it change things? On what hardware? Which operating system? Stop asking questions. There’s another version where they claim that the tests were run on an Apple M4 Max.

Why? Who knows. What does this have to do with anything that you’d actually run in production? Ah, but this is the “legacy run” version where start times are included. What does this mean, how much does it change things? On what hardware? Which operating system? Stop asking questions. There’s another version where they claim that the tests were run on an Apple M4 Max.

Great. Again, which OS? Which compiler? In this benchmark Rust is about 40% slower than C. What? How? Rust, C, C++ and Zig (along with others on this list) can all be compiled into LLVM IR. This LLVM IR is decoupled from the high-level language that was written by humans and can be compiled deterministically into machine code.

This means that for such a simple program, as long as the compiler that produces LLVM IR from the source code (C or Rust or whatever) does not do anything erroneously silly, the LLVM IR should be essentially identical. Consequently, the compiled binary would be exactly the same. Everything down to the individual instructions running on your CPU

would be the same, yet we are seeing a difference of tens of percents in runtime? For the person who’s thinking this right now: Yes, I would be very skeptical about theoretical runtime safety checks causing a 40% performance gap, and this would still only address Rust.

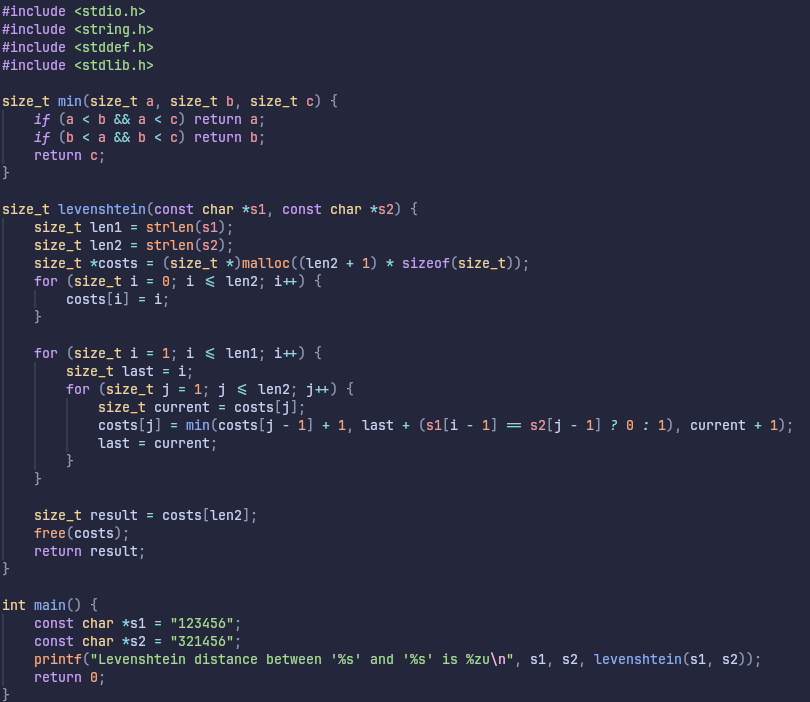

Furthermore, I’m sure you could write an implementation that is nearly if not completely the same in C and C++. In this case even the source code would match, leaving little room for even the LLVM IR compiler to mess up. In fact, here’s one example of such source code:

Great. Again, which OS? Which compiler? In this benchmark Rust is about 40% slower than C. What? How? Rust, C, C++ and Zig (along with others on this list) can all be compiled into LLVM IR. This LLVM IR is decoupled from the high-level language that was written by humans and can be compiled deterministically into machine code.

This means that for such a simple program, as long as the compiler that produces LLVM IR from the source code (C or Rust or whatever) does not do anything erroneously silly, the LLVM IR should be essentially identical. Consequently, the compiled binary would be exactly the same. Everything down to the individual instructions running on your CPU

would be the same, yet we are seeing a difference of tens of percents in runtime? For the person who’s thinking this right now: Yes, I would be very skeptical about theoretical runtime safety checks causing a 40% performance gap, and this would still only address Rust.

Furthermore, I’m sure you could write an implementation that is nearly if not completely the same in C and C++. In this case even the source code would match, leaving little room for even the LLVM IR compiler to mess up. In fact, here’s one example of such source code:

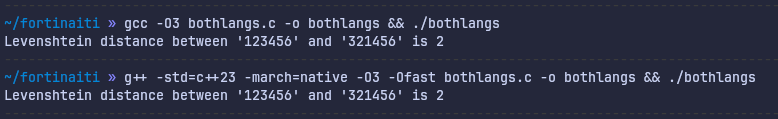

Running the binary compiled either as C or C++ produces the same result:

But I suppose this LLVM route or using literally the same source code would lead to uninteresting visualizations where the circles bounce in sync and this would not get that many likes on LinkedIn. Therefore, they compile directly to machine code with different compilers and different source code. Fair enough.

On top of this, there are an endless number of problems even with just the implementation. Which compiler flags, which language standard and/or version? Sure, you can look up the Github repository [2], but you’ll find 10 different fixes which lead to 10 more fixes. Eventually, these may eventually lead you to a house of cards where you might be able to say something about your very specific setup and how performance could look like there. That’s it. This would say nothing about the languages, the compilers, the hardware or anything else in isolation. Just about their very specific combination that you happened to converge to. You simply cannot deduce Fortran out here impressing based on one circle moving three pixels further than another circle every millisecond in an animation. None of this is even remotely sensible. And yet, the title of the site asks the most hilariously naive question you could think of: “How fast is your favorite language?”

All gas no brakes

I was aware of the Levenshtein disaster prior to looking into this. Horrid, but whatever. Maybe someone made it, had this explained to them and learned their lesson. Wrong! These people have been busy and are more enthusiastic than ever. Look at this:

Holy hell, Fortran is really out here impressing this time. Like just look at that. I’m on my way to tell my product owner about the wonderful world of Fortran and how every codebase should be rewritten right now.

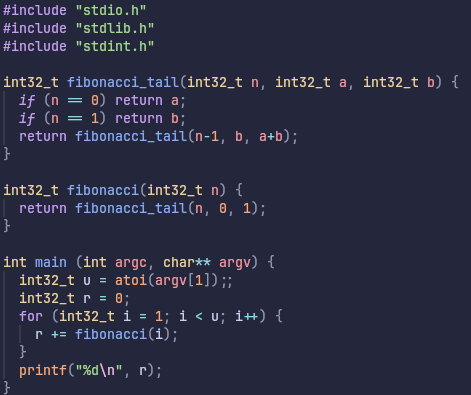

Let’s break this down. The Fibonacci sequence is a simpler problem than Levenshtein distance. You begin with the numbers 0 and 1, add them together and then sum the result with the latter of your two starting numbers. Repeat this forever. It’s just a chain of integer additions, resulting in 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and so on. This simplicity of course then leaves room for optimization. The creators have opted for a naive implementation, which in this case means recursion. Simply put, they made a function that receives two numbers, sums them and then calls itself according to the aforementioned rule until a limit is reached. Rinse and repeat, do this for a bunch of different languages and you’re on your way to LinkedIn fame.

When written this way, each new number creates a new stack frame, leading to extremely inefficient computation. The reasons you’d ever want to test the performance of such a disgusting codebase are beyond my comprehension. I guess for the fun of it, and to see what languages are blazingly fast at creating redundant stack frames and moving the program counter around aimlessly.

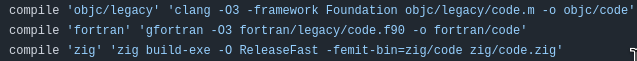

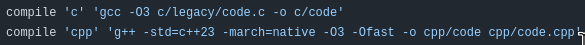

But alright then, Fortran is out here impressing. It’s able to do this so much faster than any other language. Let’s check under the hood to see just how it accomplishes this. Here’s how they compile Fortran:

and C/C++:

Important to note here, the -O3 compiler flag is the most aggressive optimization flag for GCC (the compiler project that g++ and gfortran are also part of). It basically throws everything in its cookbook at the code to make it run faster. No problems here, it’s a good thing that it is enabled.

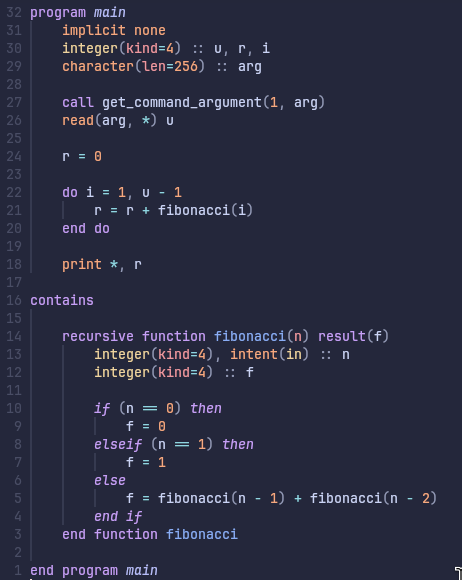

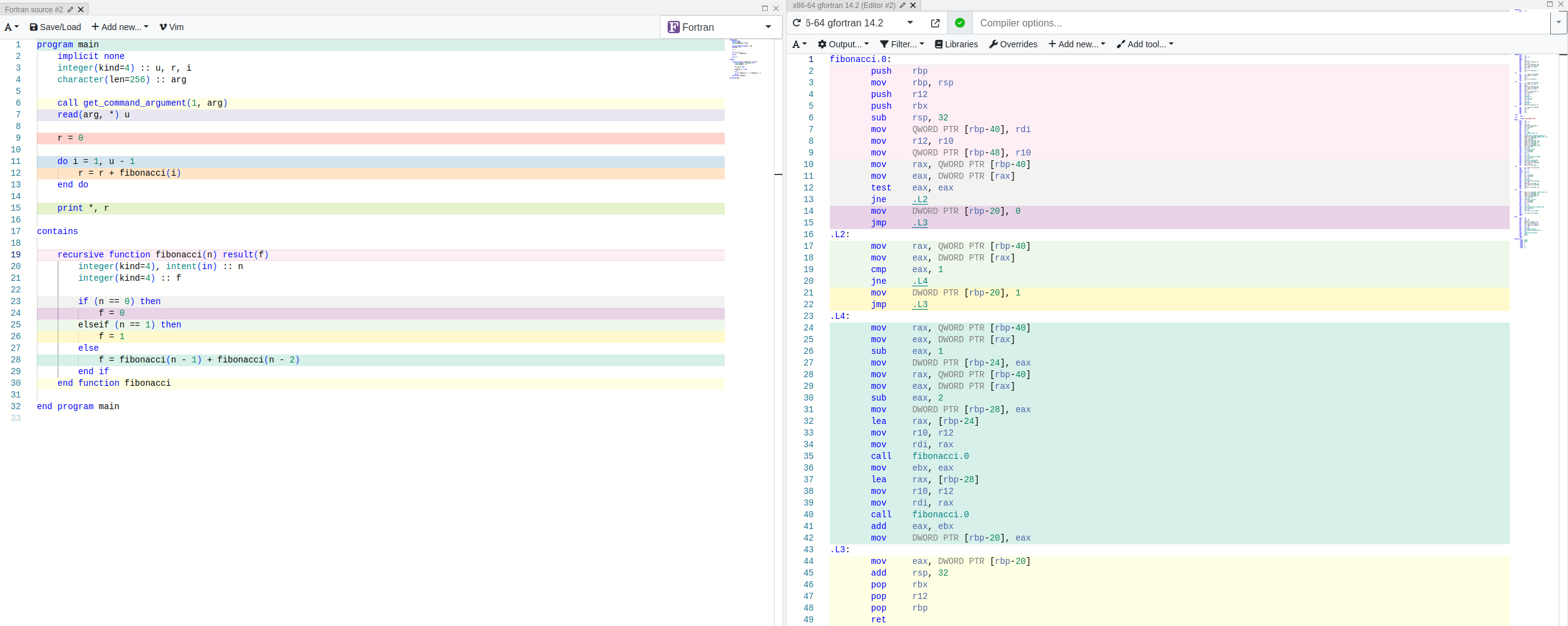

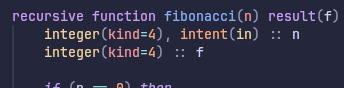

Digging deeper, here’s the Fortran code:

and C code:

Simple enough, it looks like what you’d expect. Essentially, you feed it n and it returns the nth Fibonacci number. In case you’re wondering, yes, the results are the same for both versions unlike with the Levenshtein benchmark.

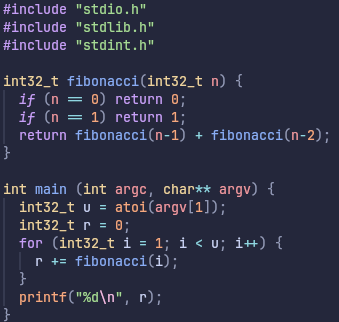

So let’s see what kind of assembly gets churned out when we compile these [7]. To keep the result simple, we have disabled optimizations here.

Feel free to zoom in to inspect the result, but I can also save you the trouble and skip to the conclusion: It’s nearly identical between the two implementations.

Most of the computation is spent within the fibonacci, .L2, .L3 and .L4 blocks so those are the ones that matter. If anything, the program compiled from Fortran seem to be doing a bit more busywork, not less.

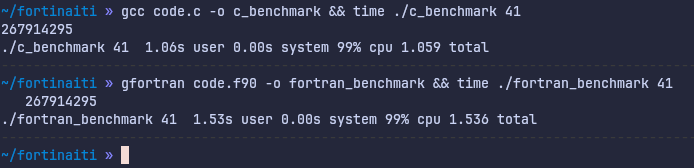

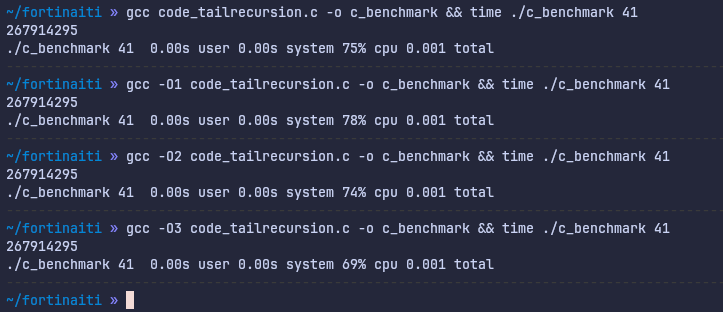

This is easy enough to confirm, and in fact the program compiled from Fortran is 50% slower than the one compiled from C on my CPU:

(As a sidenote, I am aware that running the programs wrapped with time is not the best way to benchmark them, but trust me, it won’t make a difference here.)

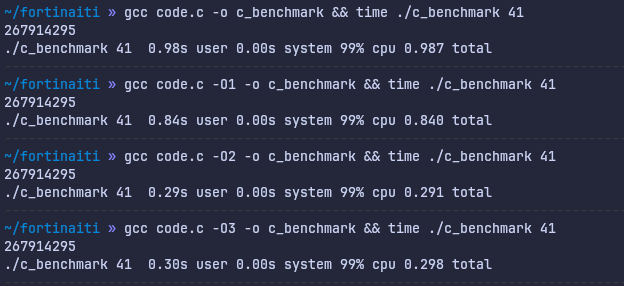

Getting back to the results, clearly this crazy difference between speeds shown in the visualization is something that happens when we start cranking up the compiler optimizations. Let’s see:

For C, it’s clearly gotten a lot faster. Especially optimization level 2 had a big jump. That’s nice. What about Fortran?

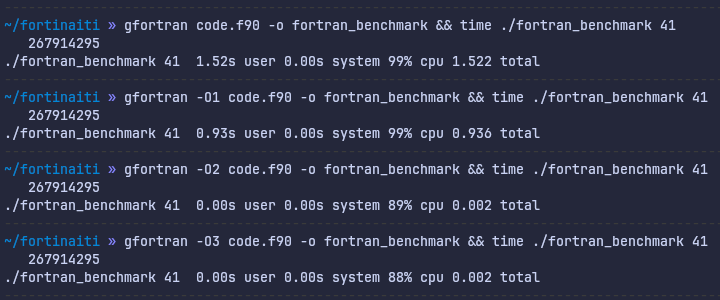

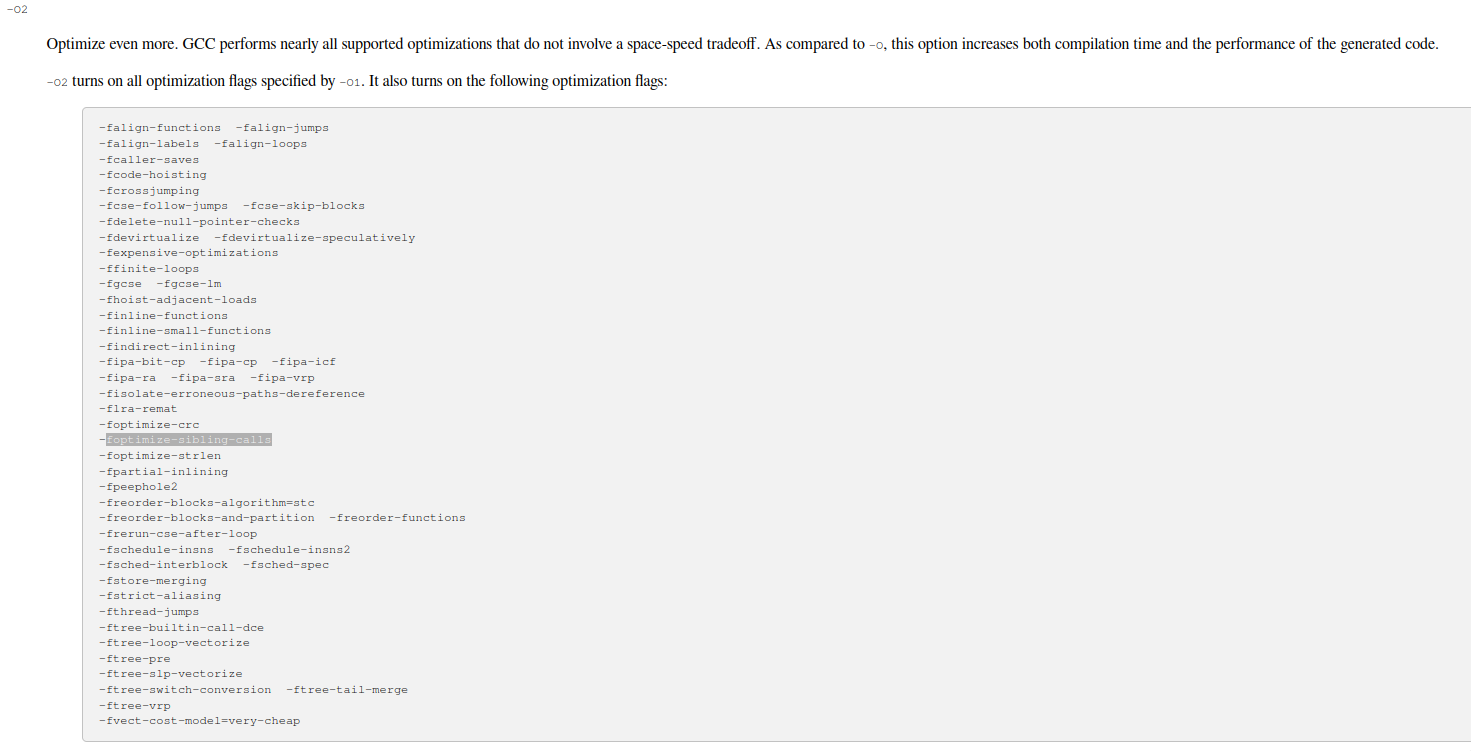

Just wow. Blazingly fast confirmed, yet again at optimization level 2. You know what, let’s dig around for just one more second. Here’s a snippet from the GCC reference [6], it shows what flags get enabled at optimization level 2:

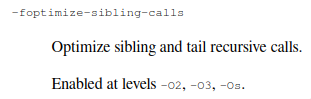

Pay attention to the highlighted flag called foptimize-sibling-calls. Here’s what it does:

So that’s the reason Fortran is the greatest? It’s just super good at optimizing tail recursion. Amazing, truly ahead of its time. But wait, how is it able to do this? Looking at the Fortran code, we specified a recursive keyword for the function…

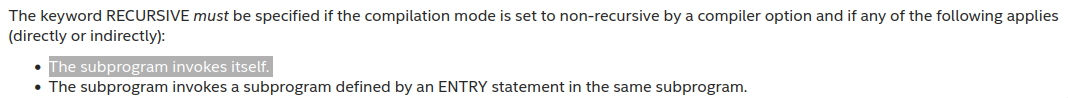

So we’re tipping off the compiler to the fact that this entire function call can be optimized away? In fact, Fortran does not allow you to call a function from within itself unless you define it as a recursive function for this very reason [5]:

In essence, Fortran does not allow the programmer to write a naive version of Fibonacci, but we’re comparing its runtime against actually naive implementations in other languages?

I’ll spare you from the optimized assembly as it’s a lot more complex, but it seems to confirm what we’re seeing. The compiler just fully gets rid of the function calls and essentially turns it into a big for loop. All because we’re telling the compiler that it can do this.

Inspired by this, let’s change the C code just a tiny bit:

We’ve split the fibonacci function into two different functions. In combination, these functions do the exact same thing. However, individually they both return the result of just one function call unlike previously, where the function returned the sum of two function calls. We are still being naive and doing recursive functions. You could argue that we’re being even more naive, we’ve added even more functions! Here are the benchmarks:

The program is instantaneous even without any optimizations. C out here impressing, I suppose. Better yet, this is also valid C++ and it runs just as fast when compiled with g++. So C++ also gets to be out here impressing. Is this starting to feel ridiculous? Hope so, because that’s exactly what this is.

Perhaps I’m being needlessly critical. As mentioned, there is also a set of “non-legacy” benchmarks, whatever that means. At the very least there we know what hardware those tests were run on. Seeing that Fortran is in fact the greatest language for high-performance computing and these results are extremely scientific and replicable, we’re going to see it shine in this one as well.

0.00 milliseconds. I give up.

(Thankfully Fortran is still more than 100 times faster than the rest)

Conclusions

I really wish people would stop trying to simplify programming language performance considerations into such a nonsensical form for the sake of social media attention. However, i wouldn’t get my hopes up about this happening. The best thing to do might be to just laugh at the ridiculousness of it all along with others [4] and move on.

Credit:

[1] https://pez.github.io/languages-visualizations

[2] https://github.com/bddicken/languages

[3] https://www.linkedin.com/posts/benjamin-dicken-78797a73_check-out-the-results-for-levenshtein-distance-activity-7275179003055951872-rGRl

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EH12jHkQFQk

[5] https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/docs/fortran-compiler/developer-guide-reference/2023-1/recursive-and-non-recursive.html

[6] https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/Optimize-Options.html

[7] https://godbolt.org/