Immutability at home

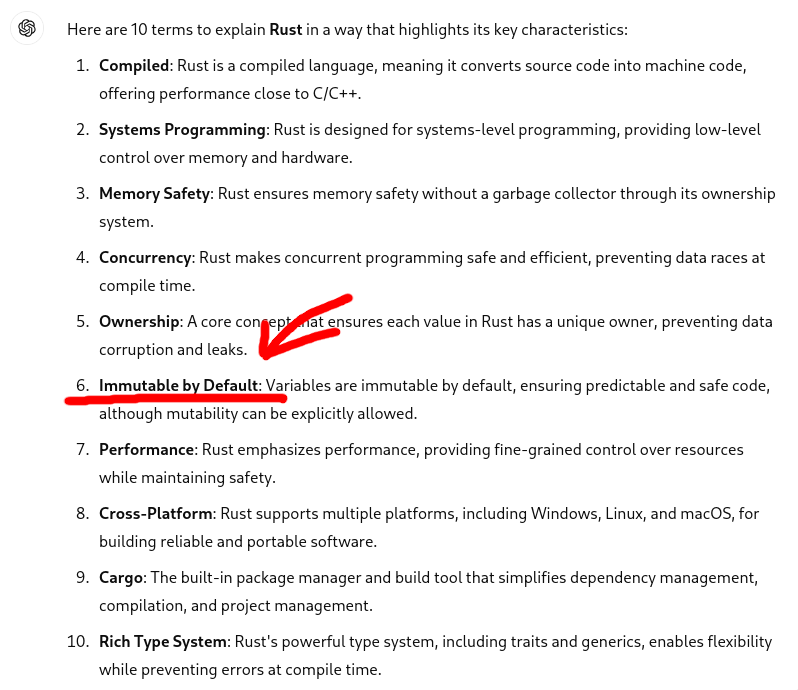

Rust is a compiled, statically typed and memory safe language where variables are immutable by default. That last part is actually quite central to the design of Rust. In fact, it’s even one of the first things ChatGPT has to say about it:

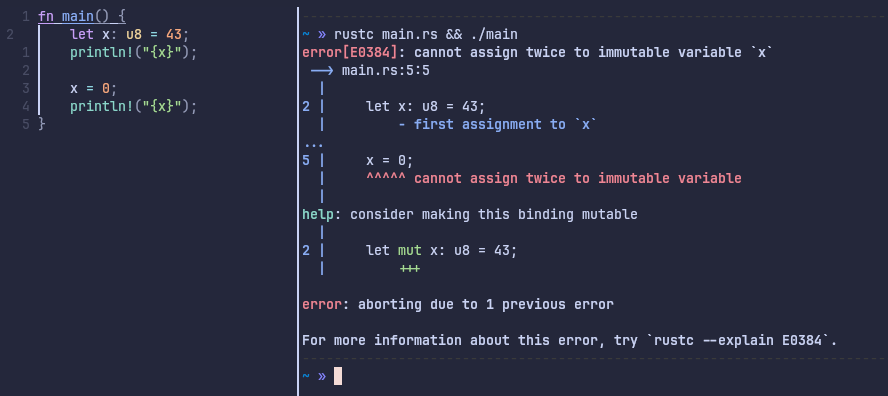

That’s great, all variables have a static type and unless you intentionally change things, that variable will be immutable. In other words, If you read a variable’s value and it’s X, that value will be X in any future reads as well. As you’d expect, the compiler will immediately complain about you trying to modify (ie. mutate) the value of an immutable variable:

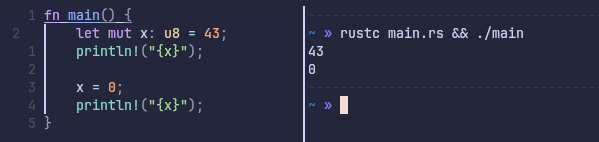

The compiler nicely points out that the way you change this behavior is by defining the variable as mutable:

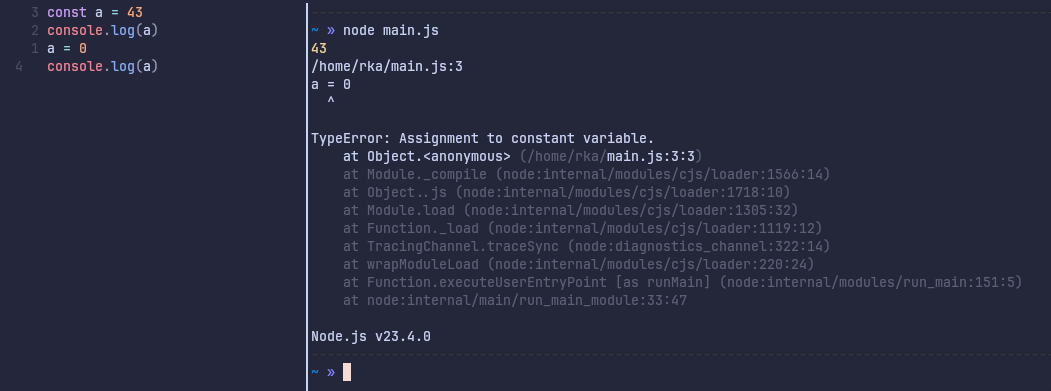

This is an important part of Rust’s type system and increases predictability, readability and error resiliency. This is not the case in dynamically typed and “mutable by default” languages such as javascript, where the following code is perfectly valid:

In such languages, you usually need to go out of your way to define an immutable variable. However, once you do, the behavior is as expected. Trying to modify a “constant” variable’s value causes an error:

Perhaps the most important result of this design decision is that it prevents erroneous code from being written. Code that abuses variables, leading to confusion and errors. This next code might look stupid but it’s actually indistinguishable from 90% of the code on npm:

In a well-designed language such as Rust the previous code would not be possible:

Uh oh.

Digging deeper

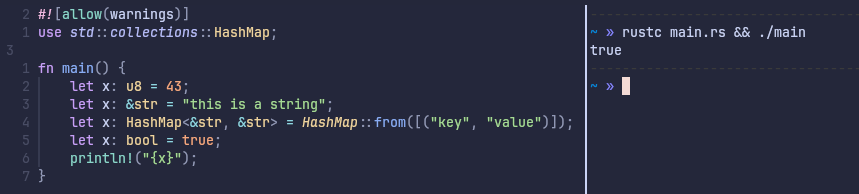

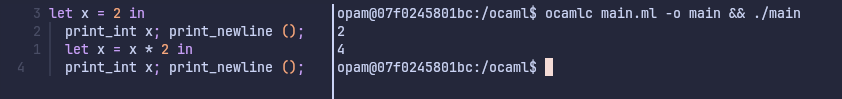

For the uninitiated, there’s no tricks going on here. The variable is not a pointer and the first line just hides compiler warnings related to unused variables. After all, the first three values of the variable are never used. The code compiles, runs and is perfectly valid.

Let’s investigate a bit further:

So the variable is in fact bound to all the intermediate values, and those values remain active within the block in which they were defined. When exiting the block, the variable returns to the value it was before the block.

How does this differ from the previous example where the compiler immediately errored out?

Immutability of values does not mean immutability of variables

Technically, we are not modifying the value of the variable. When we define let x: u8 = 2 at the start, eight bits from the stack are allocated for this integer.

Later on, when we do let x: u8 = x * 2, the righthand side is evaluated first. Obviously, we read the value of 2 from those previous eight bits and then multiply it by 2, ending up with 4.

The important distinction here is that this value of 4 is not written to the same 8 bits as the previous value. Instead, 8 new bits are allocated for this new value, and then

the variable is rebound to that memory location. We are not overwriting, we’re shadowing. If you wrote x = x * 2 instead, you would be attempting an overwrite, causing an error.

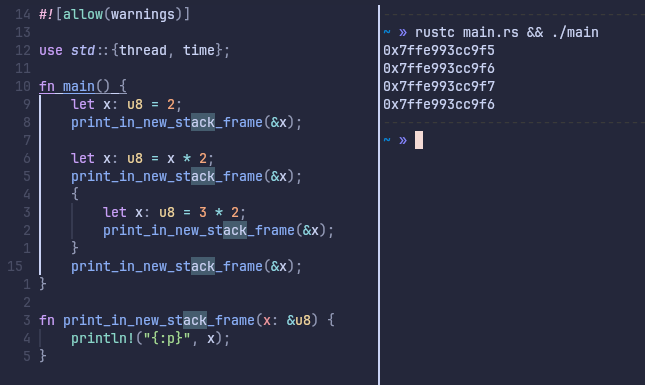

We can see this in action if we check what memory addresses the intermediate values are mapped to:

The values are at different addresses located exactly one byte apart from each other.

The separate function for calling the println macro is simply because the macro allocates 11 bytes of memory due to internal variables.

Calling the macro within a function allocates this memory in a new stack frame that gets deallocated after the function returns, making the addresses of our variable’s values adjacent. Otherwise, they would be 12 bytes apart.

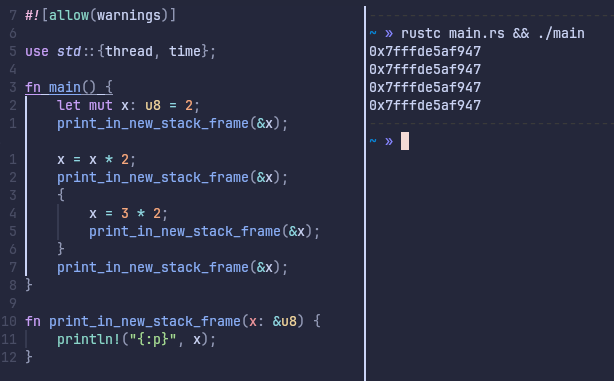

Aesthetics aside, the main point here is that if we were to do the same with a mutable variable, the address would not change:

Is this the case in other languages?

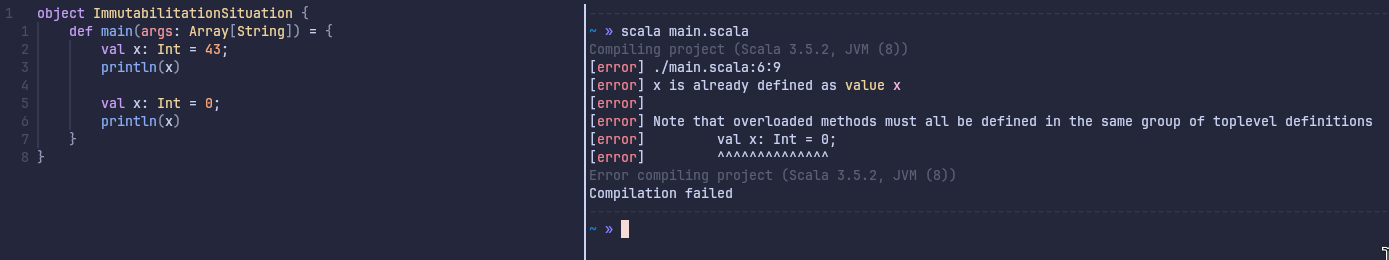

Although variable shadowing makes sense and you can wiggle your way out of any argument about it from a logical standpoint, it can definitely be seen as odd. Just as an example, Scala (another statically typed and compiled language) has no such feature:

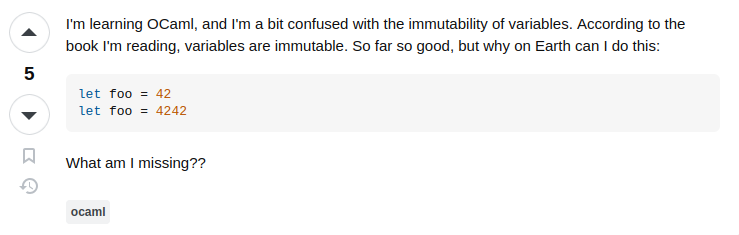

In fact, it is not easy to find another language where this is allowed. OCaml might be the most notable example of a language where something similar is possible:

Although this decision does sometimes raise equally similar confusion in its users:

Futhermore, these languages are definitely in the minority, and are seemingly all purely functional languages unlike Rust. In imperative and multi-paradigm languages, an immutable variable tends to be immutable, and not just on the basis of a technicality.

If you can’t beat them

At first, I felt this was an unnecessary footgun to add to a language whose entire ethos is about removing ways to shoot yourself in the foot. However, complaining does no good, so I’ve decided to embrace it instead. In fact, I have come to love this feature of Rust due to how much it can improve your code’s readability.

No more need to remember a plethora of variable names when less can suffice. In fact, one variable is already plenty, even when writing imperative or object-oriented code. Let’s face it, do you really need more than one variable in your program?

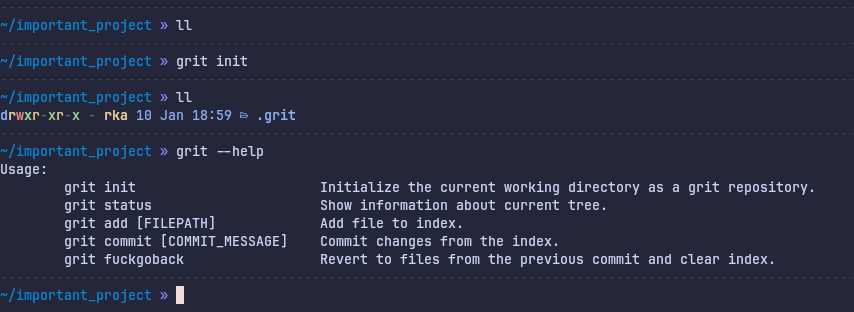

I know this revelation is not easy to accept. However, for all the developers who still have their doubts, I have prepared a demonstration in the form of a production ready and fully functional project. The project is called Grit, a bare bones version of Git that is written in Rust. Not only is it written in Rust, it’s also written using the genius way of programming that is encouraged by its design: It only uses a single immutable variable. Let’s get started.

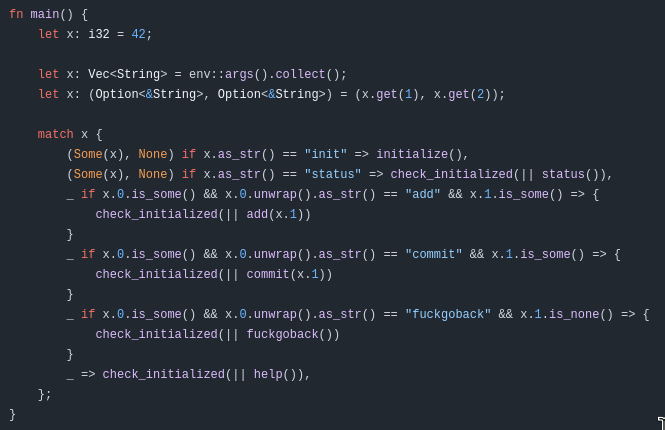

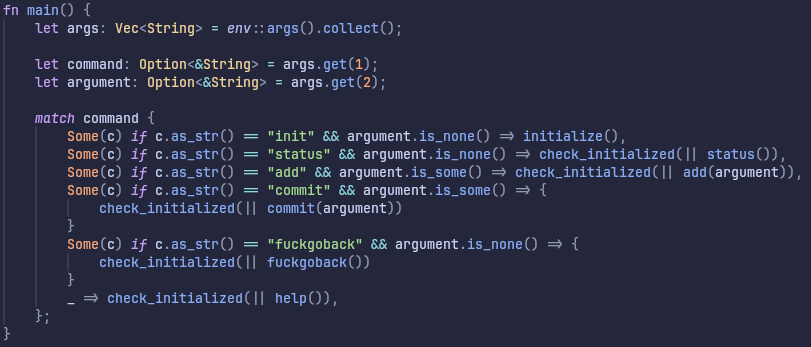

We begin in the main function. Here, we get our first taste of how using only a single immutable variable throughout your program can improve your code:

We first define x as 42. This is not necessary, but it sets us up for success.

We need to figure out what the user wants to do, so we have the opportunity to immediately rebind the variable to a vector of strings that contains the user arguments.

After doing so we have already halved the amount of variables our brain needs to remember.

It gets better, as now we have to figure out what the arguments are, if there even are any. Therefore, we rebind the variable to a tuple of two optional pointers to strings. Depending on what these options contain, we enter the correct function. All without confusing variable names and bloated logic. If you’re keeping count, you’ll notice we’ve already removed 66% of the mental overhead caused by variable names, all with a single immutable variable.

If we were to write this same code the old fashioned way, it might look something like this:

I know I never want to write code as ugly as this again. Let’s have a look at a few more code snippets.

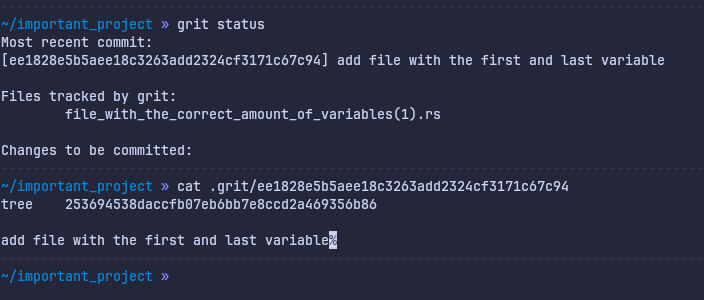

If we were to create a file, add it to the Grit index and then commit it, Grit would do something very similar to Git (an inferior project with many different variable names and not written in Rust). It first writes the file as a blob object, then writes the tree of files tracked by Grit as a tree object and finally writes a commit object of the resulting Grit state. Here is what the result looks like:

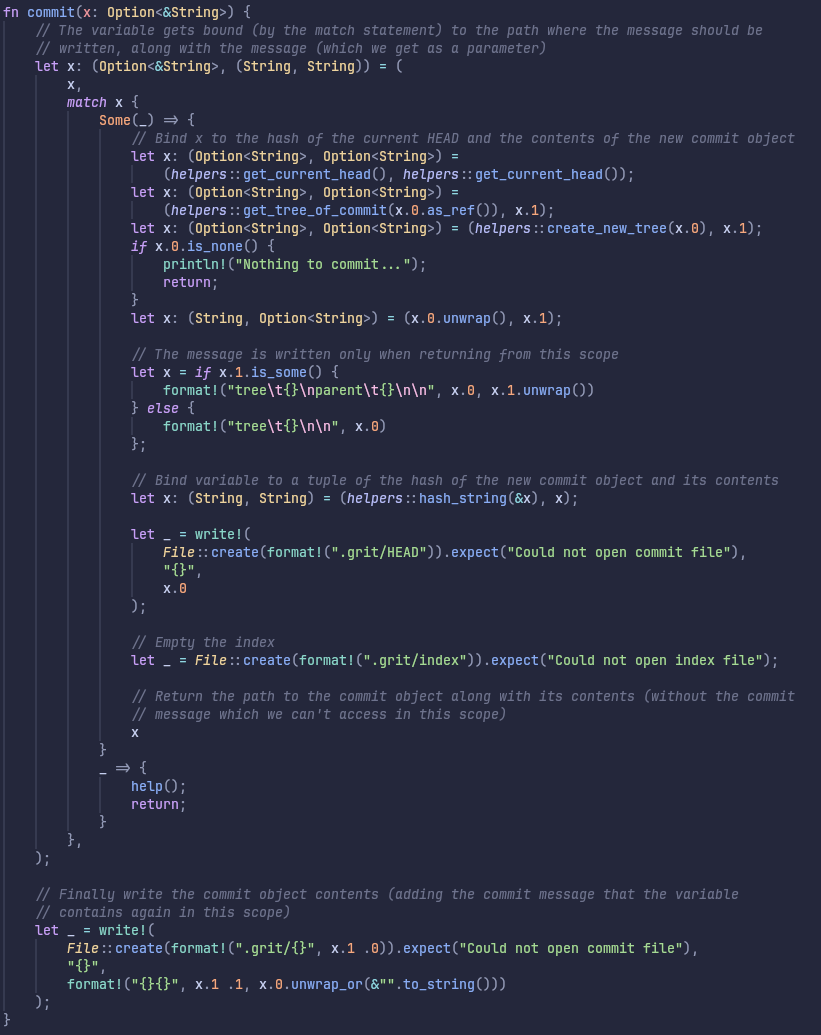

Let’s inspect the function that writes the commit file shown by the cat command:

Note that we are unable to create a File object and use it to write to the filesystem, as that variable needs to be mutable. Obviously, we are using only immutable variables to ensure that their values never change. As pointed out by ChatGPT, this ensures that the code is predictable and safe.

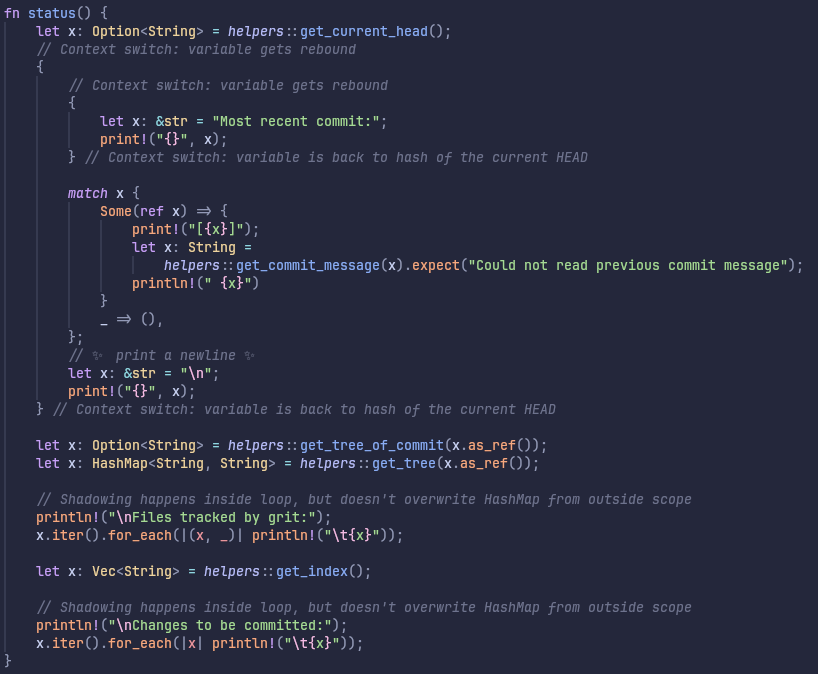

It’s a good time to mention that this code produces zero errors and zero warnings during both compilation and runtime. After all, this is the way code is meant to be written. Let’s have a quick look at the status function:

We make clever use of the code blocks, and realize that the variable returns to its prior value when exiting one. This way, we can make the code readable and style our writes to standard output, all with a single immutable variable.

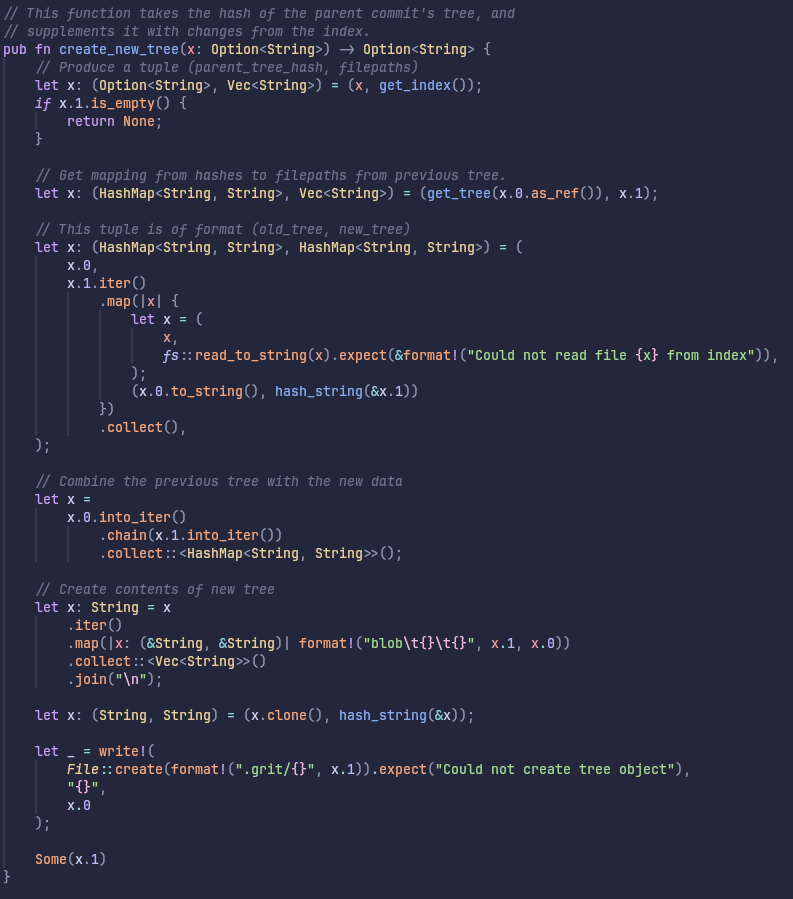

We finish our tour of the code by looking at a helper function called create_new_tree. Obviously it is a shame that we still need to remember multiple function names, and I would like to see this change in the future.

Either way, this function essentially combines two HashMaps, possibly overwriting values from one with values from the other.

Most programmers would implement this function with multiple mutable variables and by modifying the HashMaps directly. This is unsafe and the values of the variables are not predictable, unlike with immutable variables.

Wrapping up

Rust (along with a handful of other programming languages) make the term “immutability” more ambiguous than usual. In the context of programming languages, Wikipedia defines an immutable object as an object “whose state cannot be modified after it is created” [1]. The section of this article focusing on Rust only mentions

that: “By default, all variables and references are immutable. Mutable variables and references are explicitly created with the mut keyword”. This definitely leads some room for clarification.

Looking beyond the oxymoron of “immutable variable” (like saying “open secret” or “deafening silence”), there can be said to be at least two types of immutability. Immutability of variables is when a variable cannot be rebound to a new memory address. On the other hand, immutability of values is when the bits at a memory address cannot be modified, but the variable’s binding can still be changed.

In terms of variables defined with the let keyword in Rust, it is only a matter of the latter.

It is worth noting that this terminology leaves room for a situation where you would have an immutable variable, but the bits at its bound memory address could be modified as long as the variable’s binding wouldn’t change. This is exactly the case if you were to define a const int* ptr in C++ for instance.

The distinction here is that we are dealing with pointers (&u8 instead of u8), unlike in the case of shadowing.

As a final note, I am aware of the const keyword in Rust. It does not allow for shadowing, along with other features such as automatic type inference. However, its purpose is to hold global constants that remain static and are required throughout the entire duration of a program’s runtime.

This is why the only lifetime allowed for a const variable is 'static, which is the longest possible lifetime for data in Rust. This is hardly what you should be using for a variable that you need temporarily during an arbitrary code block in your program.

Even if you would like for that variable to be truly immutable, not just immutable by the way of technicality.

Credit

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immutable_object

The code can be found on in this Github repository