Reversals & Displeasure

If you didn’t know that the creator of the Fallout game series has a Youtube channel then I highly recommend checking it out. His channel is called @CainOnGames and he talks about all aspects of game development. His stories are interesting even for someone who is not in the industry and rarely plays videogames anymore. Today, I was listening to one of his videos in the background, titled Fast Fail. As the title suggests, the video is about failing fast, the form of a trial-and-error software development that includes a large amount of prototyping and incremental progress. Cain talks about it in the context of game design, where one of it’s forms is apparently referred to as “grayboxing”. The image below depicts the use of grayboxing during the development of Uncharted 4 [1]:

The term is derived from the use of primitive, untextured objects in the environment. Oftentimes, the characters don’t even have animations. Combat consists of a bunch of T-posing, unicolored humanoids shuffling about. But it gets the point across. After all, it’s just meant to show how the flow of a level works. If it doesn’t work, it’s changed. Cain mentions in another video how, while working on another game, they threw away playable, fully finished and optimized levels because they didn’t end up working out or feeling right. That’s exactly what failing fast is meant to avoid. In a perfect world you’d never have to polish something that, in the end, won’t make the cut. Removing something that took a few days is frustrating for the person who created it. Removing something that took a few months is disastrous for the entire project. The reversal only hurts more the longer you delay it.

It’s always interesting to find parallels between different crafts by listening to knowledgeable people in other fields. The more foreign the better, as even for an uninteresting field the parallels can be worthwhile. I’m a strong advocate for failing fast in professional life, yet I’ve never made a single video game in my life (this definitely doesn’t count). Before the philosophy even had a name, Cain and his team had used failing fast to make Fallout, one of the most recognizable and well-known game series ever.

Recurring theme

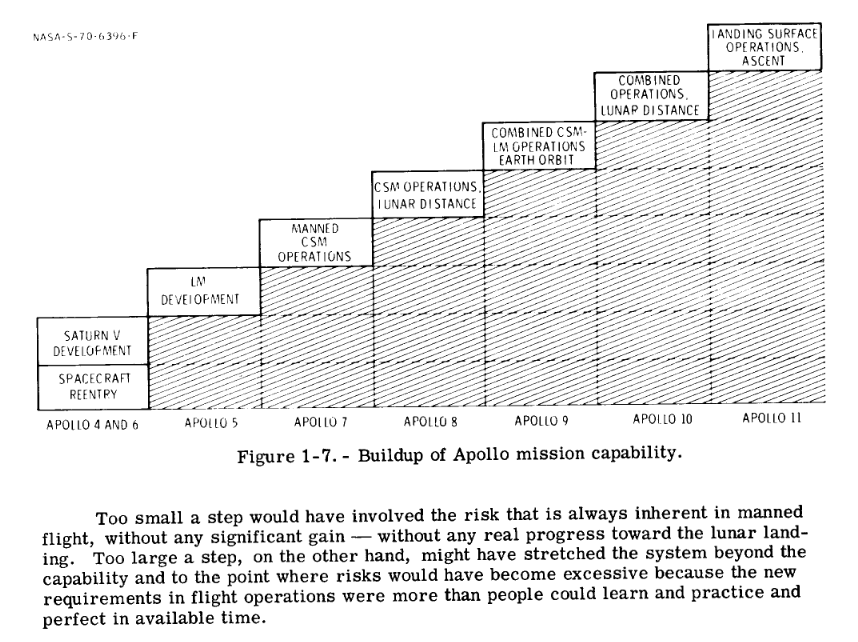

Perhaps some of the smartest people of the past century were pooled together in the 1960s. Their mission was to get humans on the moon as part of the Apollo program. It’s certainly an astonishing feat of human ability. However, what had escaped me until about a month ago is that these people made a handbook on how they achieved it. Seriously. The document is called What made Apollo a success? (1971), and there are some real gems hidden in it [4]. Even better, you could find the exact same parallels, check this out:

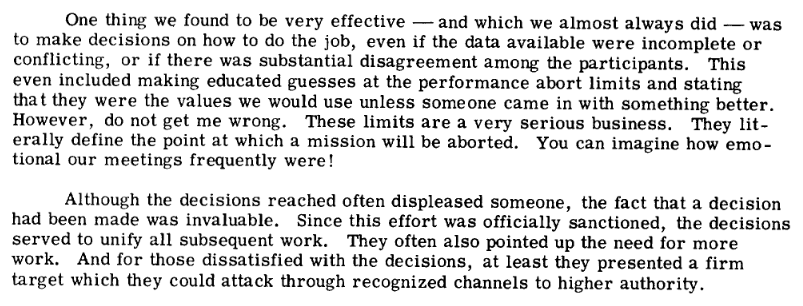

Isn’t this really cool? These are the incremental steps that the Apollo engineers planned from the beginning. Obviously, they had a goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth”, as Kennedy put it. Any task that worked towards that goal was good. Any task that worked against it was bad. If a task does not get us closer to the goal, at least it can be ruled out and we’ve probably learned something as a result. Perhaps it was even a necessary step to get to where we’re going next. Let’s jump a bit further in the document:

Decisions are the core of any successful endeavour. Oftentimes, any decision is still better than no decision. Before the empire crumbled and way before its more recent recovery, Facebook had an internal motto that says: “Move fast and break things” [2]. This is starting to seem like a recurring theme…

I first tried rock climbing when I was a kid. I wanted to always rent the climbing shoes because I thought I needed to figure out what kind of shoes I liked the most. In the end, I never bought climbing shoes. Instead I ended up using generic, worn-out rental shoes for the few dozen times I went climbing. I would try all the different types of shoes they had so I would get a feel for them. Sure, things were changing and I was moving, but not anywhere meaningful.

I started to get back into climbing a few years ago and immediately bought a solid pair of beginner shoes. Last year I had a list of problems with them. The toe of the shoes was too round and the build wasn’t stiff enough, so I couldn’t stand on smaller foot holds. The bottom wasn’t flat enough, so I had a hard time smearing (using the friction between the shoe and the foothold for stability). I knew the types of routes I could climb and what my limits were. The next step was climbing 7A routes with ever shrinking foot holds while also not destroying my feet with shoes that were too “professional”. So I bought new climbing shoes with these things in mind, and they’ve been great. Does this mean I regret buying the old ones, that I wish I had bought the new shoes in the first place and not wasted time using the old ones? Of course not, those old shoes were the only reason I was able to buy the right ones. The old shoes were not the goal, but a necessary step in getting to it. Maybe I’m still not at the goal, time will tell.

Learning decision making from computers

Computers are nice in the sense that they are always logical and are never indecisive. Given a task, they will work towards it no matter how unlikely it is to succeed. There are many things accredited with the current AI renaissance. These include the rise in computing power and more recently, the transformer architecture used in seemingly everything that makes it past preprint. On the other hand, a less mentioned part is the sheer omnipresence of gradient descent, the algorithm that makes all neural networks learn. Everything else around gradient descent is there to modify the types of things that can be learned in the first place. The algorithm is simple, loop this until convergence:

\(w_{n+1} = w_n - \gamma \nabla loss(w_n)\)

Where \(w_n\) is the variable being updated at iteration step \(n\), \(\gamma\) is a learning rate and \(loss(\cdot)\) is the loss function being minimized. Scale this to multiple variables, you have perceptrons. Scale perceptrons to multiple layers and add the chain rule, you have neural networks. Scale neural networks to billions of variables (parameters) and add the attention mechanism, you have transformers. Add trillions of training tokens scraped from the internet and some human annotation, you have ChatGPT. Irregardless of this egregious oversimplification, it all boils down to gradient descent.

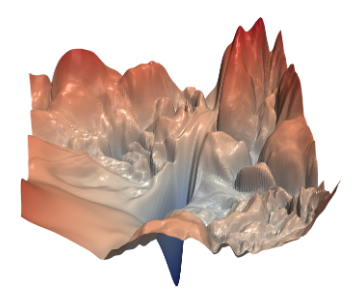

The learning rate is sometimes referred to as the step size. Increasing it makes changes during each step larger, decreasing it makes them smaller. An intuitive analogy is to think you’re on top of a foggy mountain and want to get down. The fog is so intense that you cannot see where the ground levels out, where your goal is. Therefore, you have to resort to approximations. You proceed by estimating in which direction your elevation decreases the most, moving in that direction for a bit and then starting again. Importantly, you can’t constantly change direction as re-estimating takes time and effort. There is no way to “look further” or “collect more information”, you work with what you have. Not every step is in the best direction, but by at least making steps you’re still going somewhere. Metaphorically, any non-trivial mountain is uneven. You’d need insane luck to be heading in the optimal direction on the first try. So don’t count on it, there will be mistakes. Especially for complex neural networks, the optimization landscape is extremely non-convex and not easy to navigate. Below is a visualization by Li et al. [3]:

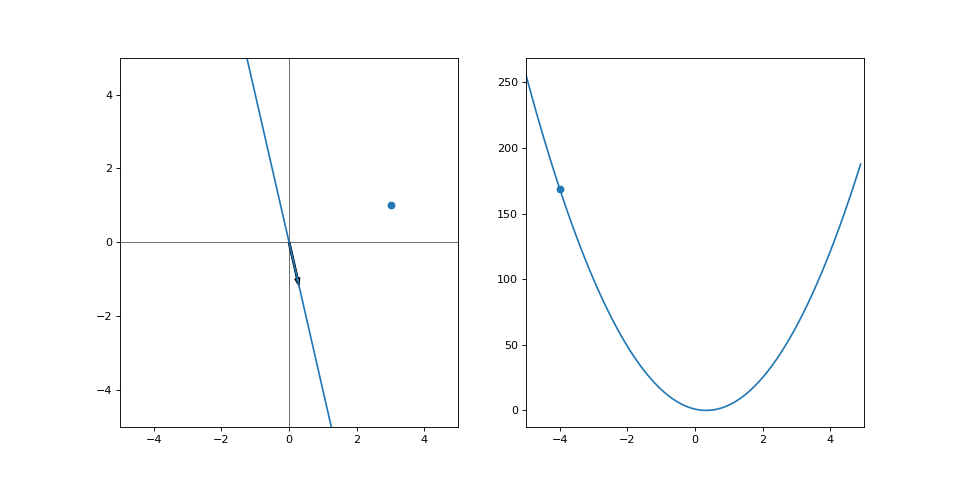

Let’s walk through an example and draw some loosely connected ideas from it. Let’s say we have one datapoint in an 2-dimensional space. This datapoint is at the coordinates (3, 1). We want to be able to predict the y-coordinate based on the x-coordinate by drawing a line. If you prefer, you can call this by its real name: training a linear regression model. Linear because it has only one degree of freedom; one free variable, and the relationship between variables is linear. Regression model because it estimates relationships between variables, namely the x and y coordinates. Change these to anything you’d like, “apartment size vs price”, “outside temperature vs number of ice creams sold”, whatever sizzles your bacon. Bottom line is, we need to predict a line that will go through this datapoint. The function looks like this: \(f(x) = \alpha x + \beta\)

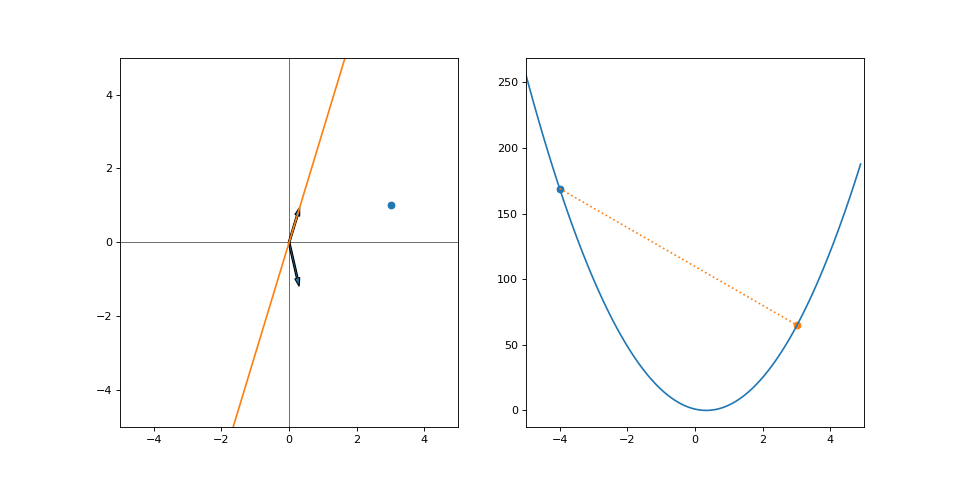

For simplicity, let’s omit the offset (\(\beta\)) parameter for now and set it to \(\beta = 0\). So we are just choosing the slope of the line. We need to start the process from somewhere, right? Let’s choose \(\alpha = -4\), our starting state looks like this:

On the left is the line that we are currently drawing, while on the right is the loss (y-axis) with respect to values of \(\alpha\) (x-axis). The loss used is the simple mean squared error, meaning \(loss(\cdot) = (y - f(x))^2\). We have only one datapoint, so it is calculated just for the point (3, 1). Here, \(\alpha = -4\) is my pair of beginner climbing shoes, the grayboxed level of Uncharted and the current approximations of performance abort limits on the Saturn V rocket. It’s not great, but it’s what we’ve got. All we can do is to look at where we are right now and approximate a direction. The gradient of the loss wrt. \(\alpha\) is:

\(\frac{d}{d \alpha} (y - (\alpha x))^2 = 2(y - (\alpha x)) - x\).

Therefore, with our one datapoint the current gradient (direction of change) is:

\(2(1 - (-4 \cdot 3)) \cdot (-3) = -78\).

Plugging it into the gradient descent step (with learning rate of 0.09) we get \(\alpha_2 = -4 - 0.09 \cdot (-78) = 3.02\):

And off we go. Our loss has decreased, so we have made it closer to the goal. But we can’t continue on our current trajectory of increasing \(\alpha\) as we’ve overshot. Does this mean that we wasted effort for every moment we went away from our goal? Or should we look at the step as a whole and realize we’ve still made progress? Let’s run this for a few iterations:

We converge quite nicely after around 10 steps despite all the “wasted” effort. Had we made smaller steps we’d still be crawling towards our goal. Had we not moved at all, well… we’d be right where we started. Was it a catastrophe that we didn’t quite predict the correct step size to instantly make it to our goal? Not at all.

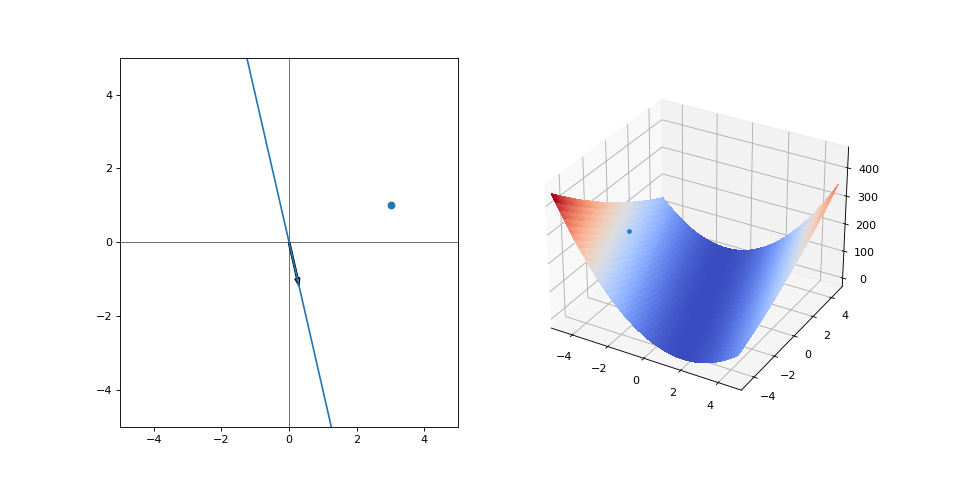

As the complexity of the task grows, so does uncertainty. Let’s free a second variable, the offset. Our function is now the full \(f(x) = \alpha x + \beta\) and the gradients are: \(\nabla_{\alpha}loss(\cdot) = \frac{\partial}{\partial \alpha} (y - (\alpha x + \beta))^2 = 2(y - (\alpha x + \beta)) \cdot (-x)\) \(\nabla_{\beta}loss(\cdot) = \frac{\partial}{\partial \beta} (y - (\alpha x + \beta))^2 = 2(y - (\alpha x + \beta)) \cdot (-1)\)

Here’s our starting state:

Now, the loss forms a 2-dimensional manifold that we need to plot in 3-dimensional space. There are many global optima. There are two variables updating at the same time. Suddenly, this has gotten pretty complicated. Surely we can’t just try something out and see where it leads. Instead, we should sit around and think about our next step ad infinitum. Doing something that turns out to not be completely right would mean wasted effort, which we should try to avoid at all cost! Well, let’s try it anyways and see what happens when we begin updating:

What a mess! Both variables jump around in what looks like an aimless scuffle! But it isn’t, every step is going towards the goal. A lot of effort is expended for such a small distance on the loss surface, but sometimes it’s the only way. The alternative is not moving or moving too slow. The former would make for a very uneventful visualization but let’s see what the latter looks like by reducing the step size:

Well at least you’re not moving too fast, right?

When you feel like failing slowly

Fast fail has it’s problems, of course. On top of the situations where it isn’t feasible and the risks are too high, some people simply cannot work while failing fast. These types of people are the perfectionists, who cannot show any of their work to others or review it critically before its fully polished. The indecisive people, who need a clear direction or else they aren’t motivated to work at all. Perhaps above all there are the misguided people who think that throwing away a piece of work means that all the effort was wasted. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Every failed prototype, deleted line of code and demo that aged like fine milk is invaluable, as long as it at least partly lifts the fog and points towards the goal. It doesn’t matter whether that goal is a piece of software, the right pair of climbing shoes, a video game or Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon.

Credit

[1] https://80.lv/articles/defining-environment-language-for-video-games/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meta_Platforms#History

[3] Li, H., Xu, Z., Taylor, G., Studer, C., & Goldstein, T. (2018). Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OoJsPvmFixU

Notes

As apparent by the post, the ability to throw around ideas, approximate their viability and move towards them without definitive proof of optimality is extremely important in my opinion. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in research. This is also the reason for the title being a reference to Research & Development. Polishing and staying stagnant mix with R&D about as well as water and oil.

Some things were left out intentionally from the post. Yes, we could visually see that the best value of \(\alpha\) in the linear regression example is slightly above 0, so the initial value of \(\alpha = -4\) is a bit adversarial. And yes, we could even calculate it to be \(\frac{1}{3}\) directly. However, in a realistic example this closed form, analytical solution cannot be inferred. Convergence is obviously not always guaranteed and the gradient updates could explode in this post’s examples. Funnily enough, Cain talks about “convergence” in his video about design by committee, referring to situations where decisions keep overriding each other. Very similar. Something else intentionally left out is the existence of local minima, that trick you into staying stagnant. These are more applicable to real life than is immediately obvious, humans are creatures of habit and can easily get stuck in old ways. However, getting stuck in local minima in a real life project is often the case of a poorly defined goal. Surely making it halfway to the moon is not the best you can do?

Also, there is an interesting discussion to be had about altering the learning rate during the optimization process, a widely used method in machine learning. In a software project, I think this is one of the main jobs of a product owner. Seeing how things are going, changing directions and keeping the process on track. However, I want to finish this post today or I’ll never get around to it. A bit of a sped up version of the Cult of Done Manifesto or an application of the Pareto principle.