Visual intuition for Fourier transforms in two dimensions

Fourier transforms are very useful. They can be used to move signals from the time domain to the frequency domain. It was Jean Fourier who, in 1807, proposed that any univariate function can be rewritten as a weighted sum of sines and cosines of different frequencies. This proposal turned out to be mostly true. What this means is that, for the most part, any function can be represented as a simple sum of sines (and/or cosines, they represent the same signal at a different phase). The remainder of this post will focus solely on the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and its counterpart, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The latter is just a fast algorithm for calculating the former. Additionally, the focus on DFT:s instead of all FT:s is due to images being represented by discrete pixel intensities instead of continous ones.

To go back to the original definition, Fourier transforms move signals from the time domain to the frequency domain. The process takes a signal whose amplitude varies as a function of time and turns it into a sum of signals of different frequencies. This sum is called the Fourier series of a signal, and expresses information of “how much” of the signal is contained within each frequency. There are a number of fantastic online resources for learning about the basics of Fourier transforms. Let’s instead focus on Fourier transforms in the spatial domain. More specifically, Fourier transforms of images that move a signal from the spatial domain into the frequency domain.

Let’s get a few definitions out of the way first. For the purposes of this post, the spatial domain is nothing more than a fancy word for the intensity distribution of pixels in our image, “the values in the image intensity matrix”. This post will only look at grayscale images (as they only have one channel) as opposed to RGB images with three channels, but know that this process is easily expandable to an arbitrary number of channels. It’s mostly a process of repeating the steps for all channels and combining the results.

The obvious answer to why the Fourier series of images are useful is this: Oftentimes the transformations we want to run on our images are computationally simpler in the frequency domain. The result of convolution in the spatial domain can be achieved with a simple multiplication in the frequency domain. So for example, applying a filter kernel on an image can be achieved by creating the Fourier transform of the image and the kernel filters, multiplying them and calculating the inverse fourier transform of the result. This result will be the same as you would get by convolving the original image with the kernel filter but the computational complexity will be lower for large kernel sizes. There are also many great resources on this topic online (a few of which are linked in the credits). However, it would be nice to gain a more intuitive feel for what the Fouerier transform of an image produces. To do that, let’s start with an image.

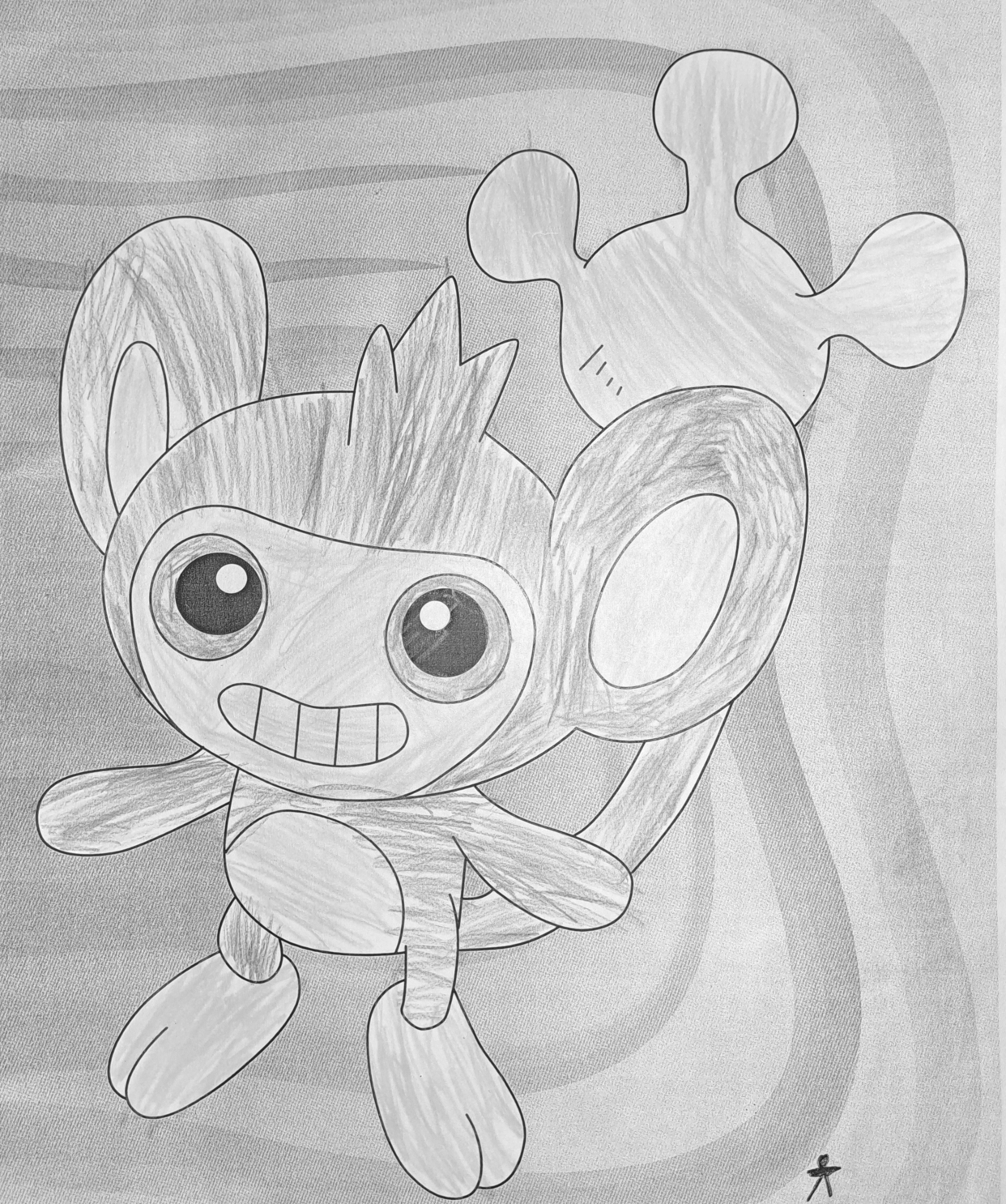

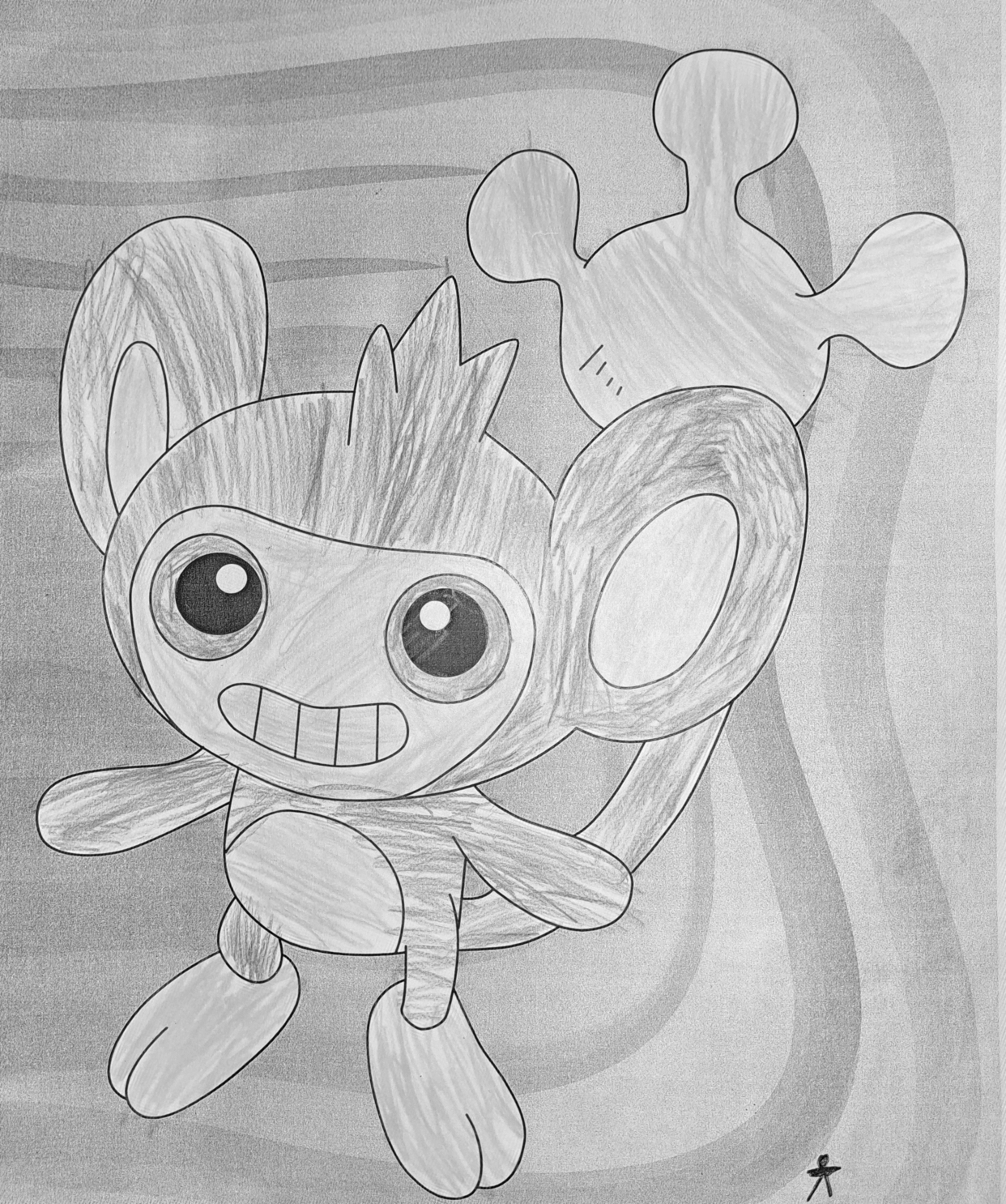

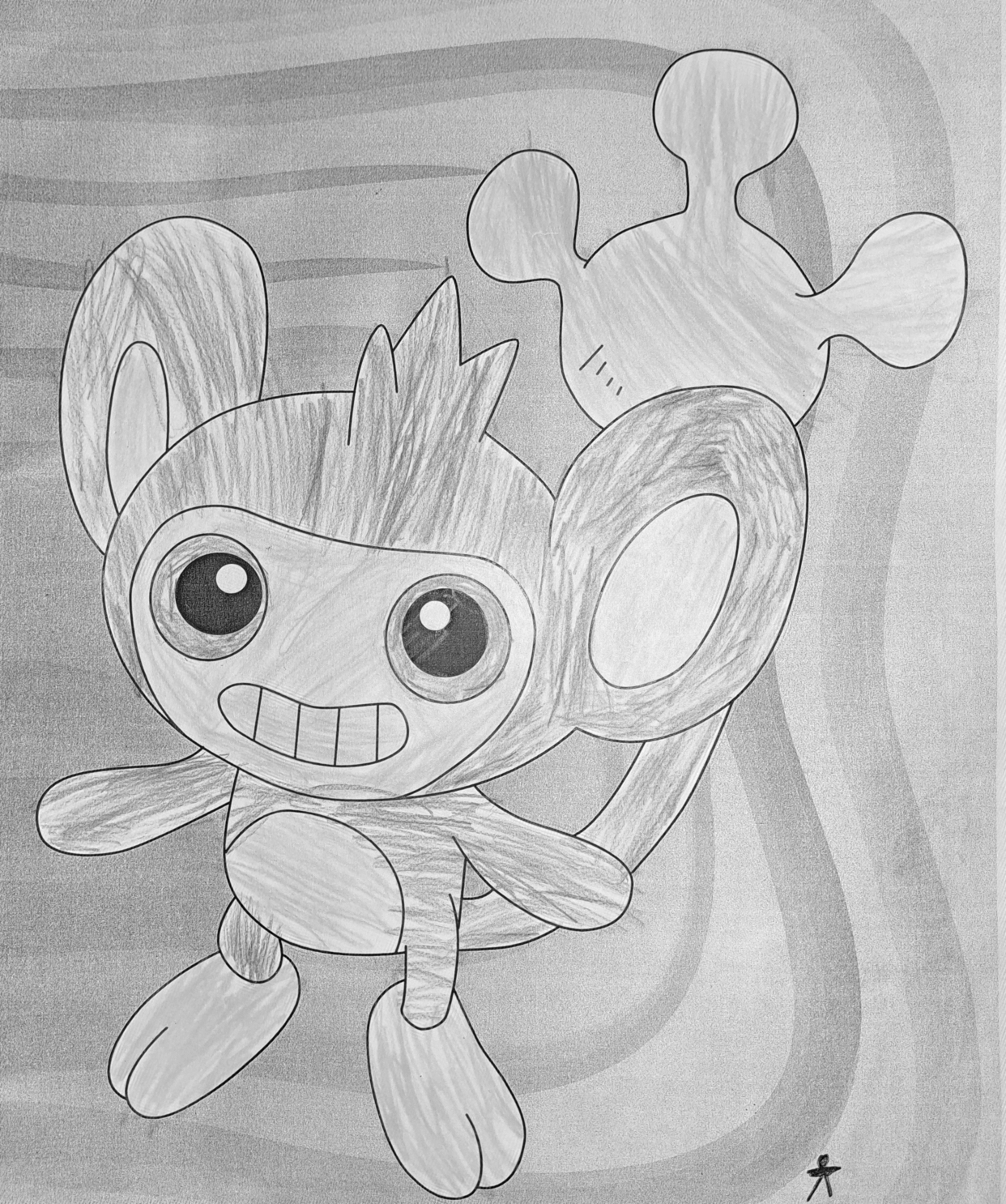

This is a photo I took with my phone. Its a cropped version of some picture printed on an A4 piece of paper I colored in as a kid. The reason for choosing this image in particular will become apparent later. Let’s tranform this image into grayscale as discussed earlier by averaging the three channels of each pixel. I’ve also halved the resolution of the image by subsampling, as it made the computations exponentially faster to run.

Remember, the result of the Fourier transform (in this case the FFT) is the Fourier series, which is a sum of sine functions with their own intensity, frequency and phase.

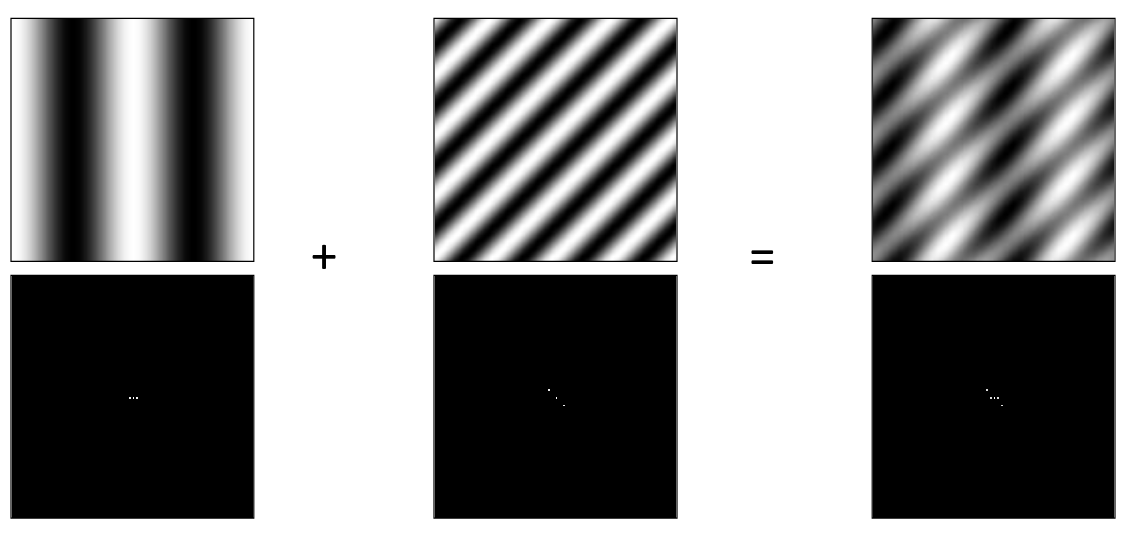

The building block of all these series is a single sine function:

A*sin(wx + p)

where A is the amplitude, w is the frequency and p is the phase of this sine function. By summing enough of these sines you can reconstruct any image. This is usually represented as a combination of magnitudes and phases, which are produced from the real and complex parts of the Fourier series

amplitude A: +- sqrt(R(w)^2 + I(w)^2)

phase p: atan(I(w) / R(w))

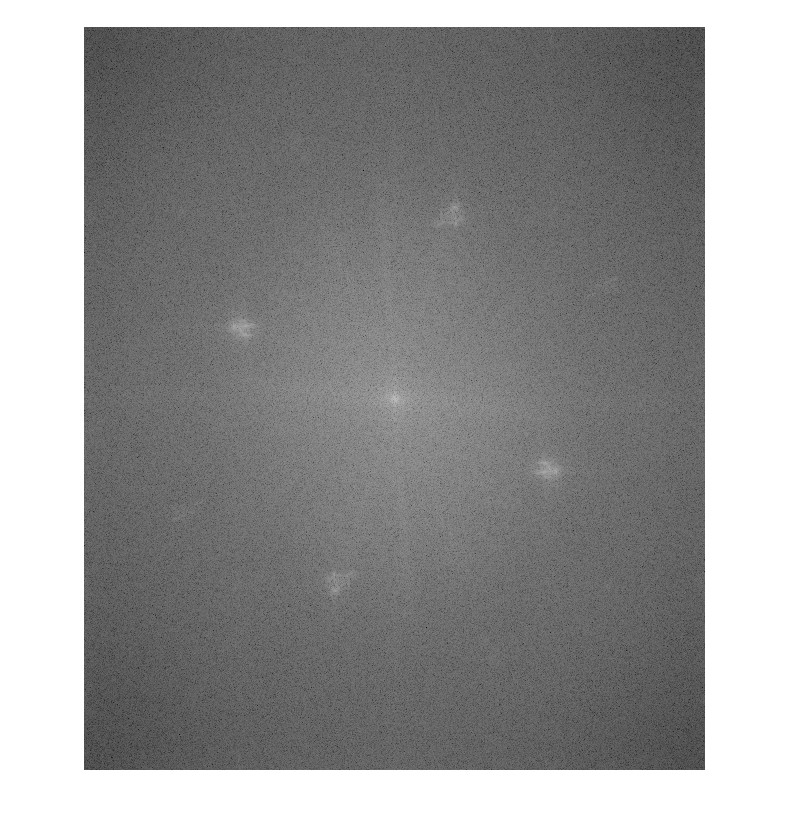

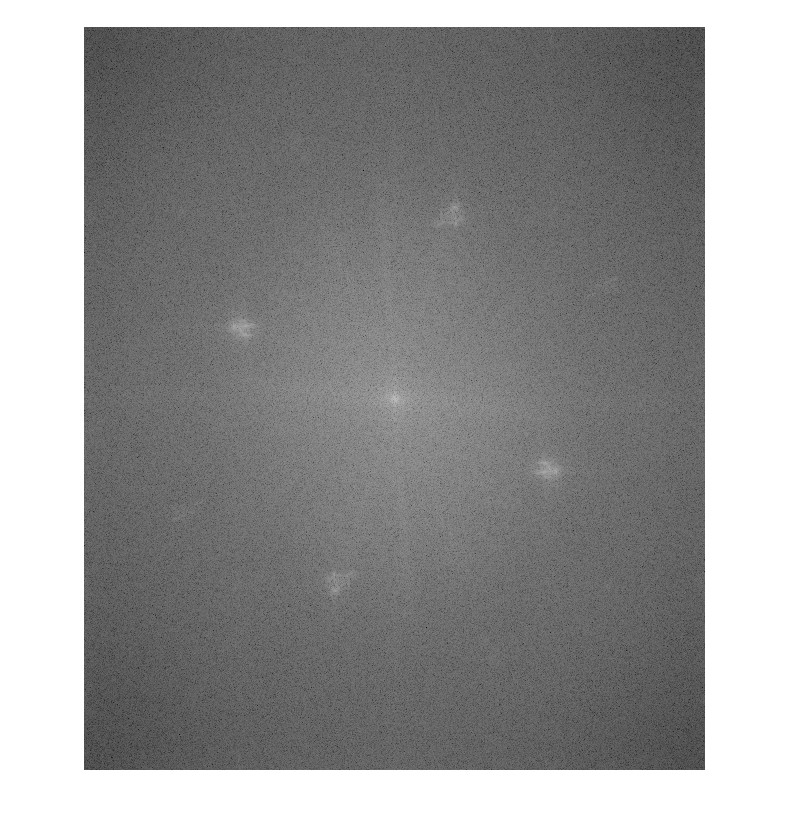

In other words, the result of the DFT (FFT) is an image with the same dimensions as the original image where the individual pixel values are complex numbers. These complex numbers have an imaginary and real part and can be formulated as two matrices, the magnitude and phase matrices respectively. The plot for the prior one, using the grayscale image above, is the following:

This plot can also be shifted such that the zero-frequency component is in the center and the frequencies grow larger the further the pixel is from the center. This together with the phase matrix form the following images:

This is a good moment to take a step back. These two images are just the results of the Fourier transform on the original photo transformed into matrices of magnitudes and phases. These matrices (images) were achieved simply by calculating the Fourier transform of the original photo, so conversely if we were to calculate the inverse Fourier transform of them we would be able to reconstruct the original image as it was without any loss of information. We have chosen an (arbitrary) 1242x1486 image of a drawing and turned it into a sum of 1845612 different sine functions, and represented those sine functions as an equal number of imaginary values. These imaginary values were then be expressed as a combination of magnitude and phase for more convenient calculations. These values were then be interpreted as pixel intensities and visualized as shown above. Not only is this process fascinating, but it’s also extremely useful in many image processing tasks.

Let’s dig a bit deeper into what the images above represent. The magnitude matrix could be seen as containing “more” information than the phase matrix because it encodes most of the geometrical features of the original image, but you need both to reconstruct the original.

In this image [2] we can see the magnitude plot of two different “clean” sine wave images. It is clear that the images consist of just one consistent sine wave, and it is expressed by the white dots symmetrically placed around the origin (which itself is just an average of all pixel densities). The distance from the origin defines the frequency and the direction defines the direction of the sine wave. The brightness of the dot marks the magnitude of that specific sine wave. The further the dot, the higher the frequency, so the more times the signal repeats. Furthermore, these signals can be combined to produce a different signal on the right. Note the change in the magnitude matrix at the bottom. Simple enough, but how can this be interpreted in our image?

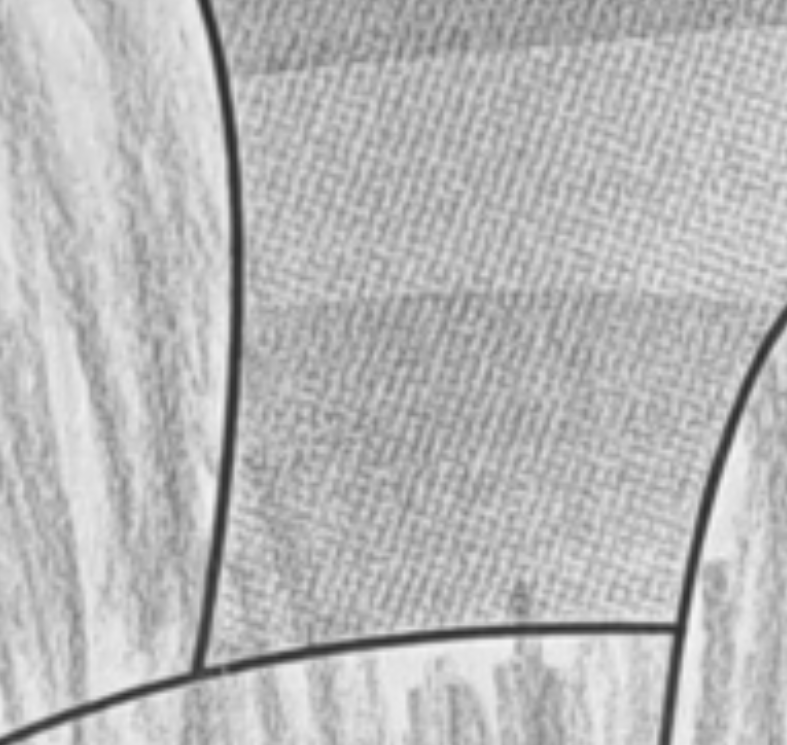

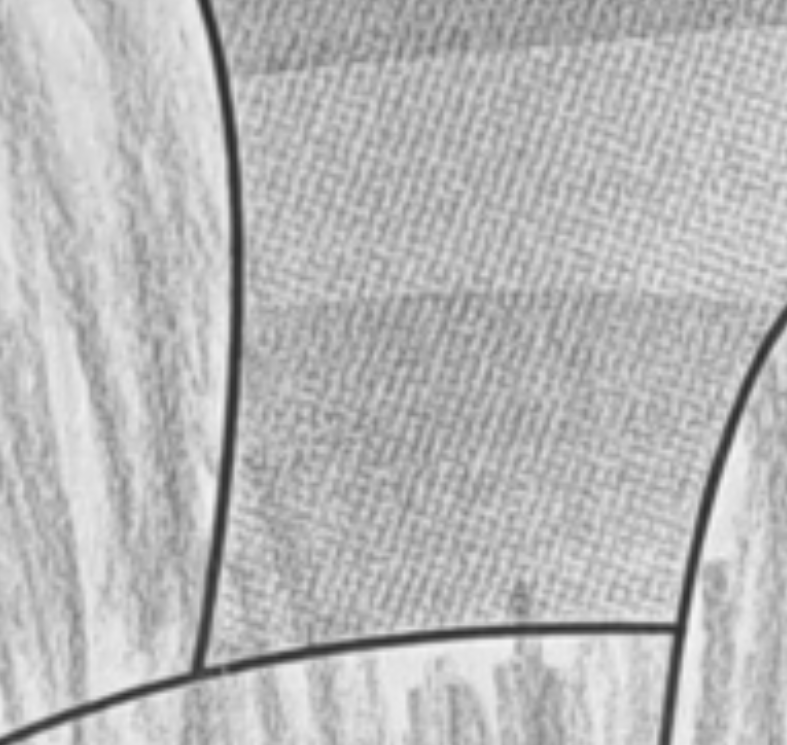

We can see that in both the shifted and non-shiften image there appears four distinct clusters of large magnitudes. They are also somewhat symmetrically placed around the origin. This means that these collections of similarly oriented high-frequency sine waves create a repeating box-like pattern in the final image. This pattern becomes apparent when zooming in:

This jagged pattern is produced by a bad printer, it’s just an artifact and noise we would like to get rid of. Question is, what if we were to reduce the intensities of those sine waves that make up the repeating pattern, and then reconstruct the image from the resulting magnitude matrix? Let’s see.

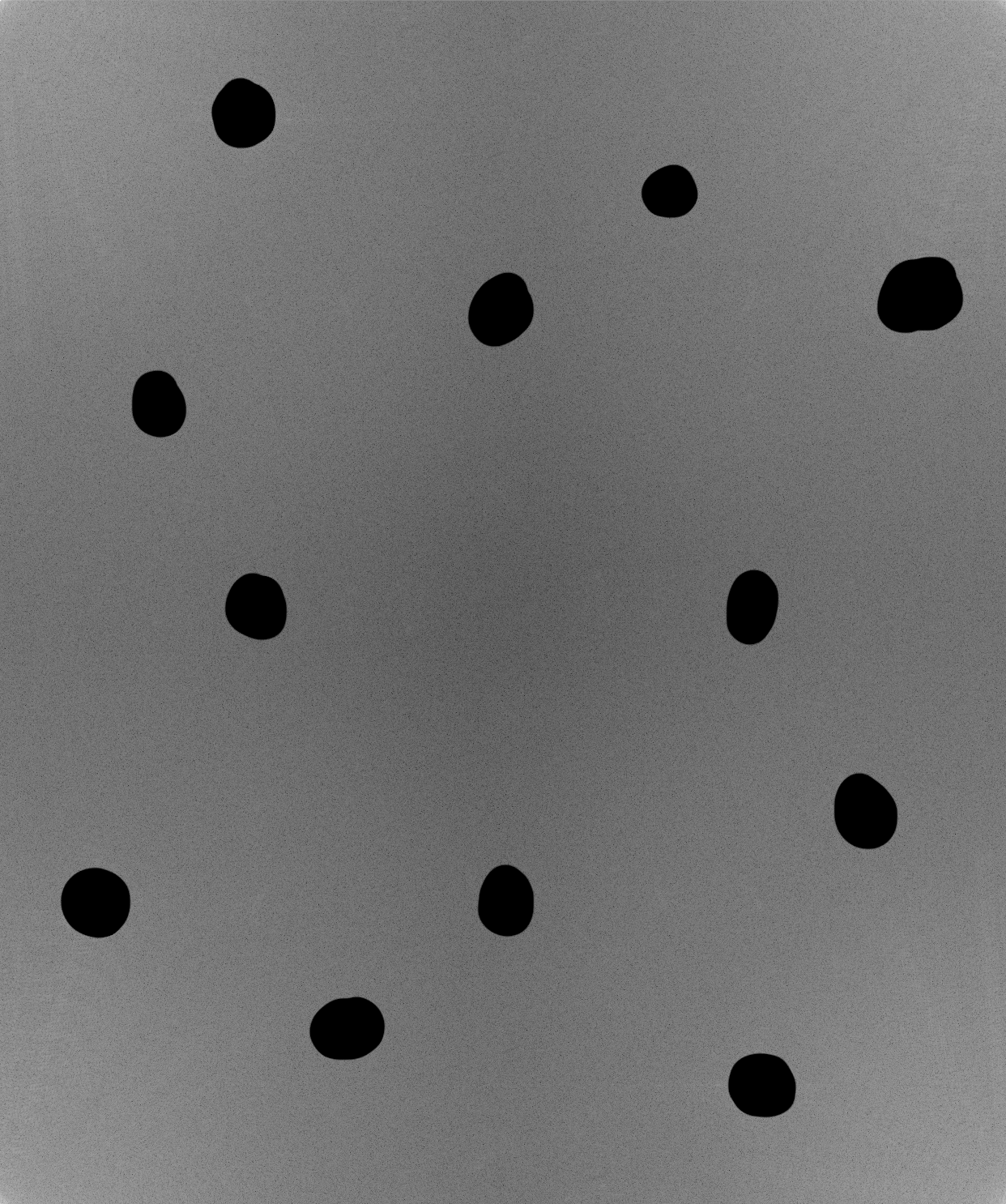

On the left is the previously seen magnitude matrix, scaled to values between 0 and 1. On the right is the reason for this post, a version that has been (very scientifically) drawn over in GIMP using a black paint brush. This has the effect of zeroing out the respective sine functions in the magnitude matrix. If you want to use a more academic image processing tool and think GIMP is not good enough for you then also feel free to use MS Paint. Now let’s calculate the inverse Fourier transform of this magnitude matrix (scaled back to original range) along with the same phase matrix of the original image.

Do you see the difference? Let’s zoom in a bit

The most important part is that none of the actually crucial information has been lost. Real world images are very noisy and definitely aren’t symmetric or uniform enough to be composed of only a few sine functions. Therefore, removing some sine waves of near-equal frequency close to each other should mostly remove these repeating patterns. Let’s zoom into the original and the resulting images and see the effect side by side:

We can see that the jagged, repeating pattern of noise has been removed. What remains is just the noise more akin to that you get from taking a picture with a cellphone camera in suboptimal lighting conditions. This is all by finding repeating noise-patterns from the magnitude part of the Fourier transform of the image, sloppily removing their respective sine signals and converting the result back into the spatial domain.

Credit

Assistant professor Juho Kannala for his lecture on Computer Vision that inspired these experiments

[1] https://www.cs.unm.edu/~brayer/vision/fourier.html

[2] https://filebox.ece.vt.edu/~jbhuang/teaching/ece5554-4554/fa17/lectures/Lecture_04_Frequency.pdf

[3] https://homepages.inf.ed.ac.uk/rbf/HIPR2/fourier.htm\

Notes

If you actually want to do something like this, zero out the clusters in the shifted image and not the non-shifted one. It’s likely going to produce a much more focused effect of removing signals from the same noise distributions. I was just lazy and didn’t want to do the inverse shift. Also, this is just a fun experiment meant to investigate the effects of modifying the results of the 2D Fourier transform. This was done mainly to gain more intuition on what they represent. If you actually want to remove noise with this method in a real setting, a more robust way to finding clusters of noise would be a good place to start. Eyeballing the image on a laptop screen will only get you so far.