Batching arises naturally from the fundamental design of neural networks

Batching is the process of passing multiple datapoints through a neural network at once. It is nearly always used in the context of training these models, where the batches themselves are often referred to as mini-batches. In this context, it is crucial for both computational efficiency and convergence of the training process. However, the former motivation also applies to inference, meaning that batching is also at the core of using any neural network after training.

This post is about neural networks and how batching is a natural by-product of their design. We will walk through some of the steps that led to the design of modern neural networks and what each step looked like from a computational point of view. Everything will be explained from the ground up, so there are no prerequisites beyond a bit of linear algebra.

Laying the groundwork

The individual units of “intelligence” used in “artificially intelligent” systems today did not come out of nowhere, but instead had an evolutionary process. First came the McCulloch-Pitts neurons in the 40s, then the perceptrons in the 50s, and finally the neurons that we know today from MultiLayer Perceptrons (MLP) in the 80s. Let’s skip the McCulloch-Pitts neurons as they are not terribly relevant, and begin with the perceptrons.

Let’s define $i$ as the dimensionality of the input vector ie. the number of features. Mentally you can replace this with anything you’d like. For the sake of an example, I’m going to use the price, gas mileage and production year of some car. In all simplicity, a perceptron consists of a weight vector $\boldsymbol{w} \in \mathbb{R}^{i}$, and a bias $b$, which is just a scalar value. Then, given a feature vector $\boldsymbol{x}$, we take the dot product $\boldsymbol{x} \cdot \boldsymbol{w}$ and sum it with the bias $b$. So, with the (arbitrary) weights $\boldsymbol{w} = [-2, 1522, 8]$ and bias term of $10$, our feature vector $\boldsymbol{x} = [10000 \text{ (€)}, 10 \text{ (l/100km)}, 2000]$ produces the following result:

\[\boldsymbol{x} \cdot \boldsymbol{w} + b = [10000, 10, 2000] \cdot [-2, 1522, 8] + 10 = 11230\]The values used could just as well be floating point numbers. I’ve used whole numbers just for the sake of simplicity.

These two operations are then wrapped in a function that outputs 1 if its input is greater than zero, and 0 otherwise. The fancy name for this is the Heaviside step function. Here, the perceptron would therefore return 1. Again, this could mean that this car is worth purchasing, or whatever you’d like. This is all a perceptron is; take in a vector of features, and map it into a scalar that signifies some interpretation of the features. This simplicity is both a blessing and a curse - it means that we can guarantee convergence, but also that we cannot solve any system where the data is not linearly separable. Even modeling a simple XOR function is not possible for this perceptron.

Increasing the units of intelligence

Let’s increase the number of these perceptrons, say, by two. So now we have three perceptrons, all of which take in the same vector and map it to a scalar value using their respective weights and biases. Each perceptron is trying to interpret some different thing. Let’s say they’re interpreting whether the car is worth buying for three different people, all with different desires and requirements. Passing a feature vector through the three perceptrons could be done separately for all of them, simply by repeating the aforementioned process of taking the dot-products and summing the results with the biases.

However, we can also stack the (columnar) weight vectors on top of each other, creating a matrix, and multiply its transpose with the feature vector. After also combining the biases into a column vector and summing it with the output of the vector-matrix product, we have calculated the results of all three perceptrons, prior to the Heaviside step function.

More concretely, with the (arbitrarily chosen) weights and biases

\[\boldsymbol{W} = \begin{bmatrix} -2 & 1522 & 8 \\ -3 & 111 & 23 \\ 3 & -3263 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \boldsymbol{b} = [10, 0, -44]\]the same feature vector passes through as follows:

\[\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{W}^T + b = [10000, 10, 2000] \begin{bmatrix} -2 & 1522 & 8 \\ -3 & 111 & 23 \\ 3 & -3263 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^T + [10, 0, -44] = [11230, 17110, -2674]\]You will notice that the first value is $11230$, just like before. If we were to take the Heaviside step function, we would see that the first person should buy the car (as we already knew) along with the second one, but the third person should not. But let’s forget about the Heaviside step function for now, and just look at the values produced.

We have mapped our feature vector into an output vector containing three unique interpretations of the features, calculated using three perceptrons. As we have omitted the Heaviside step function, let’s change the name of our units of intelligence from perceptrons into neurons. What we have produced is perhaps the simplest, and without question the most foundational component in modern artificial neural networks: the linear layer. These are otherwise known as Fully Connected (FC) layers, dense layers, affine layers, Feed-Forward (FF) layers or seemingly any other word salad you could to come up with. Naming conventions in machine learning follow the long, traditional engineering approach of None.

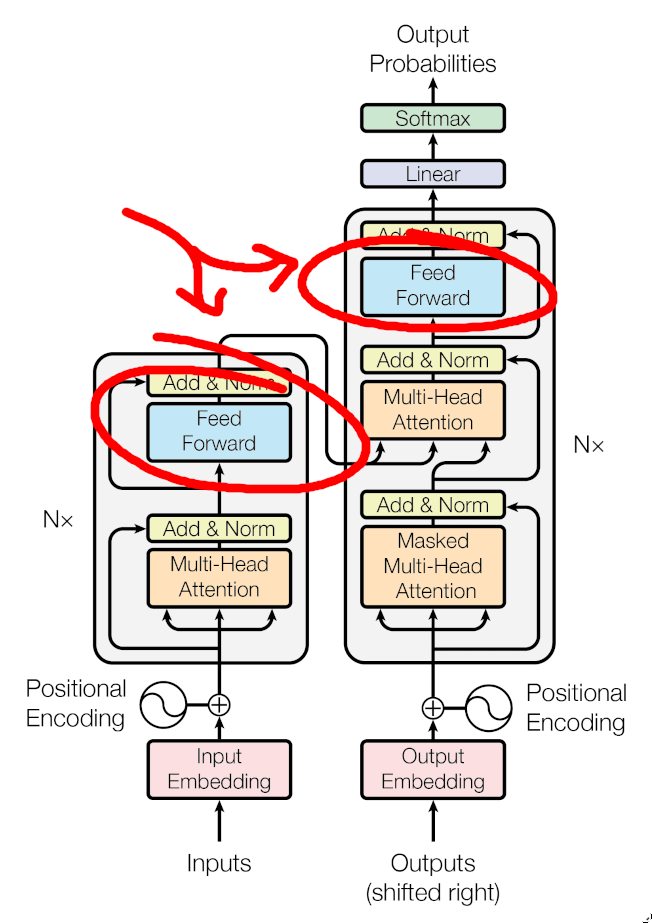

These linear layers can be chained together with a non-linear function of your choice between them to already produce some fairly powerful decision makers. Combining at least two of these layers is what is referred to as the previously mentioned Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) or alternatively, a Feed Forward Network (FFN). This was the original meaning of the term neural network. Although this term has evolved to mean many different types of architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), a form of the MLP is still present within nearly all of them. This includes the transformer architecture used universally by large language models:

Bumping up the dimensionality

Now, let’s say we have four feature vectors we want to pass through the layer. Keeping up with our previous analogy, let’s say we have four different cars whose suitability we want to evaluate for the three people from before. If we process each vector independently, this means roughly four times the work from before: A cycle of loading the feature vector into VRAM, performing the two computations, and then writing the resulting vector back into RAM. This is not the best way to do things, as we can do something very similar to how we processed multiple perceptrons at once.

Let’s create a feature matrix, which is simply the concatenation of the feature vectors. The bias vector acts a bit odd here, as it needs to be added row-wise to the matrix. Linear algebra libraries typically express this through a process known as broadcasting. However, in terms of mathematical notation, this is the same as if we were to stack copies of the row-vector on top of each other, forming a matrix where the number of rows equals the number of datapoints, and then performed normal element-wise addition. Therefore, let’s define it as such here.

With the feature vectors (cars) of $\boldsymbol{x}_1 = [10000, 10, 2000]$, $\boldsymbol{x}_2 = [5500, 15, 1988]$, $\boldsymbol{x}_3 = [78000, 32, 2021]$ and $\boldsymbol{x}_4 = [100000, 25, 1999]$ we have this feature matrix:

\[\begin{bmatrix} 10000 & 10 & 2000 \\ 5500 & 15 & 1988 \\ 78000 & 32 & 2021 \\ 100000 & 25 & 1999 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Passing it through the linear layer from before, made up of three neurons representing our candidate buyers…

\[\boldsymbol{X} \boldsymbol{W}^T + \boldsymbol{B} = \\ \begin{bmatrix} 10000 & 10 & 2000 \\ 5500 & 15 & 1988 \\ 78000 & 32 & 2021 \\ 100000 & 25 & 1999 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -2 & 1522 & 8 \\ -3 & 111 & 23 \\ 3 & -3263 & 0 \end{bmatrix}^T + \begin{bmatrix} 10 & 0 & -44 \\ 10 & 0 & -44 \\ 10 & 0 & -44 \\ 10 & 0 & -44 \end{bmatrix} = \\ \begin{bmatrix} 11230 & 17110 & -2674 \\ 27744 & 30889 & -32489 \\ -91118 & -183965 & 129540 \\ -145948 & -251248 & 218381 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]This time around, the first row is identical to our previous result, which was what you’d get by passing the first feature vector through the linear layer alone. This notion is true for the other rows as well, we would get the same result by passing their respective feature vectors through the model on their own. We have not altered the results, we have just calculated them in one big operation. Continuing with our logic, the first and second people should buy one of the first two cars, and the third person should buy one of the later two cars.

In total, we have passed four different feature vectors through a network of three neurons in one matrix-matrix multiplication and addition. In the naive approach we would be performing 12 operations using seven different vectors. What does this decrease in the number of individual operations actually do for us in practice, if anything? After all, we’re still doing the same number of raw calculations.

The shovels of the urban goldrush

I wrote a post about matrix multiplications within CUDA. It is quite relevant to this discussion, but I wouldn’t consider it to be a prerequisite as it is also needlessly in-depth.

The bare minimum to understand for the purposes of our purposes is this: modern GPUs are able to calculate large matrix-matrix products extremely efficiently. This is because the matrix-matrix multiplication lends itself really well to parallelization. If we are able to turn our model from many small dot products into a large matrix-matrix multiplication, we are able to tap into this efficiency.

In fact, we are sometimes able to process many datapoints in a way where processing all of them is roughly as fast as processing just one of them. In our example, evaluating four feature vectors for three perceptrons would be just as fast as evaluating one feature vector for one perceptron. In theory, one could scale the number of parallel workers and memory indefinitely, allowing ever-larger matrix multiplications to be computed in rougly the same amount of time. This is the magic of parallelized matrix multiplications.

Connecting the dots

The neural network arose from the following evolutional chain:

- Perceptron

- Layer of perceptrons

- Sequence of perceptron layers

This process maps exactly to the following operations:

- Dot product and a scalar sum

- Vector-matrix multiplication and a vector sum

- Matrix-matrix multiplication and a matrix-matrix sum

Early perceptrons and MLPs weren’t designed with GPUs or batching in mind. In fact, none of this was even an afterthought. All that mattered was increasing the capabilities of the models, not how fast they could be utilized. However, in doing so, the mathematics just so happened to map perfectly to operations, which are exceptionally favorable from a computational viewpoint. There’s something wonderful about the fact that this evolution accidentally leads our models to distill into a few executions of one of the most parallelizable mathematical operations in existence.

Notes

It may happen that batching is vital to the convergence of your training but batching is not possible due to memory constraints. In this situation, you can always set your batch size to 1 and add gradient accumulation. This way, you’re training as if you had a big batch size without actually posessing the hardware for it. As long as you can calculate the forward pass and hold the gradients for one datapoint, you can have as big of a batch size as you wish, at least from the training perspective. It goes without saying that the training will take much longer this way.